A name is not a person, nor is it simply a reference to that person; it is a description that influences behavior. Michel Foucault stated that “one cannot turn a proper name into a pure and simple reference. It has other than indicative functions; more than a gesture, a finger pointed at someone, it is the equivalent of a description” (105). If a name, rather than being a “reference” is a “description,” we need to ask ourselves what names describe.

Last names, such as “Quixote” and “Richardson,” indicate cultural traditions: the first Spanish, the second English (or Anglo-American). In Culture, Behavior and Personality (1982), professor of psychology Robert A. LeVine defines “culture” as

an organized body of rules concerning the way in which individuals in a population should communicate with one another, think about themselves and their environments, and behave toward one another and toward objects in their environment. The rules are not universally or constantly obeyed, but they are recognized by all and they ordinarily operate to limit the range of variation in patterns of communication, belief, value, and social behavior in that population. (LeVine 4)

While a culture’s body of rules is not absolute – we see lots of variation – culture tends to direct and limit communication, attitudes about self, perception of environment, belief systems, social interaction, and behavior. Names do not create culture, of course, but they do act as cultural identifiers. If a woman of Guatemalan descent with the name “Barrientos” is born and grows up in America speaking only English, she will still encounter cultural expectations from both Latino and non-Latino peoples, as Tanya Barrientos explains in “Se Habla Español” (2004). The name does not define her entire experience, but it certainly affects how she understands herself and how others see her. Consider what expectations these surnames of friends who grew up in America invoke: Langlois, Schoenwetter, Stein, Sniecinski, Soggliuzzo, and Kim.

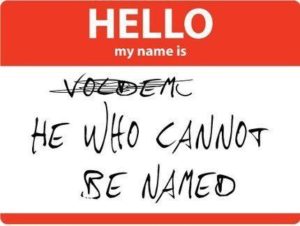

“What’s in a name?” asks Juliet in Shakespeare’s tragedy, as if to dismiss the importance of a surname. “It is nor hand, nor foot, / Nor arm, nor face, nor any other part / Belonging to a man” (Romeo and Juliet, Act II, Scene 2, lines 40 – 43). Juliet may have thought a name was something that is written on a piece of paper, easily torn apart. By the end of the play, however, she got the point.

A surname also suggests a preexisting family structure and heritage. Families are miniature cultures with their own rules, behavior, and language. The branch of Richardsons I swing from involved a conservative Mormon upbringing with many restrictions, for example against coffee, Coca-Cola, even chocolate (since they all contain caffeine, a drug), but it also has a rich culture of silliness, punning, imagination, reading, education and philosophical debate. Family culture strongly influenced our language. Not only could we not say words like “damn” and “hell,” we could not say their equivalents “darn,” “dang,” and “heck,” which my family rightly recognizes mean the same thing. We also invented words to replace “poo” and “pee.” In my family, we used to “saw” and “lumble.” A penis, when it has to be referred to, was called a “lumbler.” My place in this family culture as indicated by my last name strongly influenced my attitudes, language and behavior as a child, and even now that I have moved away from the Mormon religion.

Since those of us from English-speaking countries do not usually get our mother’s maiden names (I am a lucky exception; I got my mom’s as a middle name: Broderick), last names also indicate gender imbalances. The family is the man’s, and he is in charge. As mentioned, children get family names from both parents in Spanish-language countries, but from the fathers of each. The primacy of the male side of the family is still asserted, although Spanish names may indicate a closer connection to mothers.

First and middle names are added, often referencing other family members, living or dead, again emphasizing a place in a family structure. Frequently names say something about how parents expect the child to be, such as “Christian” or “Candy.” Nobody names a kid “Judas” or “Jezebel” (at least not at first). I recently dreamed about a little girl named “Vagina.” “What are you doing, Vagina?” her parents called across the playground. “Don’t touch that, Vagina!” Not a likely name, yet we have no qualms against “Virginia,” a name derived from “virgin.”

Most names announce gender. The declaration influences colors, costumes, toys, words, hand gestures, attitudes and jobs. Judith Butler, poststructuralist feminist, wrote in Gender Trouble (1990) that “the gendered body is performative” (Butler 2496).5 The label “boy” is more than a description of genetics or physical attributes. “Boy” is a linguistic concept, a role that must be performed. I remember being taught to look at my fingernails with my fingers curled against my palm, rather than with my fingers stretched out like a woman. I learned to hold my books at my side, instead of resting them on my hip. Such behaviors were not instinctual. I did not naturally acquire these behaviors. The command “Act like a man!” is telling. If we have to “act,” then the role is not natural. If we must act “like” a man, this implies not only that we are not one, but also that we cannot act as one; we can only act similarly. “We’re born naked,” singer RuPaul said, “and the rest is drag.” We may blur our assigned gender roles, even change sexes, but we must perform with or against that first designation. We can never wholly escape it.

Names are used in different ways to indicate different roles. Depending on the form, I behave differently. I use my full name, Ronald Broderick Richardson, during important ceremonies, such as a baptism, wedding or funeral. Ronald B. Richardson is my official persona, the one that pays taxes and votes. Strangers who want my business call me Mr. Richardson. Ron Richardson is my teaching name, at once alliterative and casual. Ron is how most address me. A few friends call me Ronny.

Knowing somebody’s name means you have some power over them. You can get their attention in a crowd, you can scold them, you can “friend” them on social network sites, you can ask them out for a date, and you can turn them in to the police. Even a pseudonym is a handle on a person, since it refers to the same body. Police can more easily to track down “Twitch” than “a guy with greasy hair and a squint.” Changing a name never makes one anonymous.

Besides proper names, nicknames also get attached to people. Here are some of mine: The (which stood for “the handsome boy, the righteous boy, the hardworking boy”), Little Lonny Leaguer (unfortunately derived from Ronald Reagan), Ronald McDonald, Donno, Duck, the Do-Ron-Ron, Bob (Boy on Bus), Storm, Man Prop, Ronosaurus Rex, and Spongy. Each of these names say something about how others see me or expect me to behave, or how I want to portray myself.

Other story words soon follow: “He’s a thumb-sucker, a brother, a playmate, a middle child, a dreamer, a tattletale, a friend, a saint, a nerd, a writer, a Taurus, a rebel, a hippie, a joker, a teacher, a boyfriend, a ghoul.” Of course, we humans are not restrained by our labels: liberals may vote like fascists and doctors may act like lovers. Roles are never absolute. But when we step outside of familiar roles, we startle, shock and scandalize. Still, if you can’t break character once in awhile, be you knight-errant or dilettante, your self-characterization is two-dimensional, and you are a poor writer of yourself. So mix it up.

Names precede the person and influence the roles we humans play. We may play along with or resist these terms, but they are difficult to escape. When we manage to remove some of our labels, as did Alonso Quixano, we merely trade them for others. We can never stand naked before the world without names and labels. We are lost in fiction, like Don Quixote de la Mancha, because we are fictions ourselves. If names are fictions, then a change of names can mean a change in destiny.

(An extract of my book Narrative Madness, edited by Katie Fox, which you can get at narrativemadness.com or on Amazon.)

Works Cited

Butler, Judith. “From Gender Trouble.” The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism. Ed. Vincent B. Leitch. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2001. 2488 – 2501. Print.

Foucault, Michel. “What is an Author?” The Foucault Reader. Ed. Paul Rabinow. New York: Pantheon Books, 1984. 101 – 120. Print.

LeVine, Robert A. Culture, Behavior and Personality. 2nd ed. New Jersey: Aldine Transactions, 1982. Print.

Shakespeare, William. Romeo and Juliet. The Riverside Shakespeare. Ed. G. Blakemore Evans. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1974. 1055 – 1099. Print.