(An extract of my book Narrative Madness, edited by Katie Fox, which you can get at narrativemadness.com or on Amazon.)

The Machiavellian Prince of Primates

Many other species are social as well, so why didn’t they develop sophisticated systems of symbolic communication? Primate societies developed language because of the exaggerated complexity of our manipulative social interactions. The MIT Encyclopedia of Cognitive Sciences says that “primate social relationships have been characterized as manipulative and sometimes deceptive at sophisticated levels” (Wilson and Kiel). Writes Kerstin Dautenhahn, biologist and professor of computer science, paraphrasing Frans de Waal, “Identifying friends and allies, predicting behavior of others, knowing how to form alliances, manipulating group members, making war, love and peace, are important ingredients of primate politics.” A hominid skilled at manipulation would be better suited than its more submissive counterparts to win resources, sex and power.

Many other species are social as well, so why didn’t they develop sophisticated systems of symbolic communication? Primate societies developed language because of the exaggerated complexity of our manipulative social interactions. The MIT Encyclopedia of Cognitive Sciences says that “primate social relationships have been characterized as manipulative and sometimes deceptive at sophisticated levels” (Wilson and Kiel). Writes Kerstin Dautenhahn, biologist and professor of computer science, paraphrasing Frans de Waal, “Identifying friends and allies, predicting behavior of others, knowing how to form alliances, manipulating group members, making war, love and peace, are important ingredients of primate politics.” A hominid skilled at manipulation would be better suited than its more submissive counterparts to win resources, sex and power.

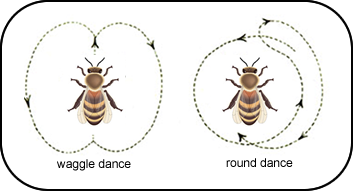

Well, yes. The language of the bees still astounds scientists. Bees communicate symbolically in the form of a dance, passing on information about distance, difficulty and value of potential food sources. They dance in the present about past experiences in order to exploit future resources. Other bees do their little dance, explaining alternative sources of pollen, and then somehow the bees come to a decision about the best source. An insect, a creature from the lower orders – far down the hierarchy of animals (at the top of which we have placed ourselves) – can clearly tell stories and make value judgements about them. (Read all about it in biologist and sociologist

Well, yes. The language of the bees still astounds scientists. Bees communicate symbolically in the form of a dance, passing on information about distance, difficulty and value of potential food sources. They dance in the present about past experiences in order to exploit future resources. Other bees do their little dance, explaining alternative sources of pollen, and then somehow the bees come to a decision about the best source. An insect, a creature from the lower orders – far down the hierarchy of animals (at the top of which we have placed ourselves) – can clearly tell stories and make value judgements about them. (Read all about it in biologist and sociologist  Since language is inherently narrative and its stories strongly influence our perception and actions, it is important to understand what narrative is.

Since language is inherently narrative and its stories strongly influence our perception and actions, it is important to understand what narrative is.