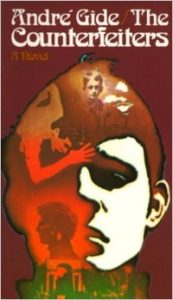

A book within a book, a play inside a play, a picture in a picture, these are examples of mise en abyme, a literary term the French writer André Gide borrowed from heraldry. Pronounced “meez en a-beem,” it literally means “placed in the abyss,” or, more simply, “placed in the middle,” and it was used to describe a shield in the middle of a shield, as in this coat of arms of the United Kingdom from 1816-1837. (Image from Wikipedia.)

A book within a book, a play inside a play, a picture in a picture, these are examples of mise en abyme, a literary term the French writer André Gide borrowed from heraldry. Pronounced “meez en a-beem,” it literally means “placed in the abyss,” or, more simply, “placed in the middle,” and it was used to describe a shield in the middle of a shield, as in this coat of arms of the United Kingdom from 1816-1837. (Image from Wikipedia.)

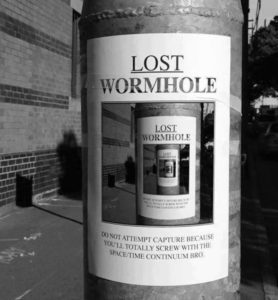

You’ll notice that the shield inside the shield has another shield inside of it. You can imagine yet another inside that one and so on and so on, forever and ever, so I like to think of “mise en abyme” as “into the abyss.” The eye travels down the rabbit hole to infinity, as in this photo of a “Lost Wormhole” from Illuminaughty Boutique’s post “38 Mise en Abyme GIFs that Will Make Your Brain Bleed… OR WORSE.”

You’ll notice that the shield inside the shield has another shield inside of it. You can imagine yet another inside that one and so on and so on, forever and ever, so I like to think of “mise en abyme” as “into the abyss.” The eye travels down the rabbit hole to infinity, as in this photo of a “Lost Wormhole” from Illuminaughty Boutique’s post “38 Mise en Abyme GIFs that Will Make Your Brain Bleed… OR WORSE.”

Continue reading “Into the Abyss: The Mise en Abyme, the Art Work Within the Art Work”

Makers of false coins are not the counterfeiters that most concern André Gide in his novel The Counterfeiters (Les Faux-Monnayeurs). The counterfeiters that matter most are the writers: the character Édouard, the narrator who speaks for Gide, and even Gide himself. The fictional Édouard writes at length in his journal about a book he is planning to write, a book called The Counterfeiters, which shares not only the same title as Gide’s novel, but also its subject and themes. Nevertheless, The Counterfeiters is not a book within a book as many critics claim because the reader is never allowed to read Édouard’s novel, only his notes.

Makers of false coins are not the counterfeiters that most concern André Gide in his novel The Counterfeiters (Les Faux-Monnayeurs). The counterfeiters that matter most are the writers: the character Édouard, the narrator who speaks for Gide, and even Gide himself. The fictional Édouard writes at length in his journal about a book he is planning to write, a book called The Counterfeiters, which shares not only the same title as Gide’s novel, but also its subject and themes. Nevertheless, The Counterfeiters is not a book within a book as many critics claim because the reader is never allowed to read Édouard’s novel, only his notes.

This introduction to Donald Barthelme’s short story “The School” is non-fiction. Non-fiction means “not fiction.” Fiction, as you have learned, is a story that is “not true.” In other words non-fiction, on a linguistic level, is “not not-true.” This means, logically, when you cancel out the negatives, that the non-fictional information I am about to give you, is — I am very pleased to say — true.

This introduction to Donald Barthelme’s short story “The School” is non-fiction. Non-fiction means “not fiction.” Fiction, as you have learned, is a story that is “not true.” In other words non-fiction, on a linguistic level, is “not not-true.” This means, logically, when you cancel out the negatives, that the non-fictional information I am about to give you, is — I am very pleased to say — true.