At the end of the 1941 John Huston film The Maltese Falcon, based on the Dashiell Hammett novel, Sergeant Tom Polhaus asks Sam Spade about the heavy, black statuette of a falcon that was the cause of all the mystery and murder.

“Heavy,” he says. “What is it?”

Our hard boiled detective, Sam Spade, replies, “The, uh, stuff that dreams are made of.”

In one of the most faithful adaptations in film history, this line stands out because it was not from the book. Humphrey Bogart suggested the line, thereby transforming the black bird from a mere MacGuffin, a plot device to drive the action, into an allusion to Shakespeare’s The Tempest, theater, literature, art, and the artificiality of life. (We’ll come back to Prospero’s speech after a closer look at the bird.)

What is the Maltese Falcon?

Hammett probably based his statuette on the Kniphausen hawk, a ceremonial pouring vessel, made by an unknown artist around 1697 for George William van Kniphausen, Count of the Holy Roman Empire, of silver, encrusted with red garnets, turquoises, sapphires, citrine quartzes, emeralds, amethysts, and onyx.

Hammett probably based his statuette on the Kniphausen hawk, a ceremonial pouring vessel, made by an unknown artist around 1697 for George William van Kniphausen, Count of the Holy Roman Empire, of silver, encrusted with red garnets, turquoises, sapphires, citrine quartzes, emeralds, amethysts, and onyx.

What makes precious metals and stones so valuable? Steel is sturdier and can shine as much as silver when polished. Cut glass sparkles as much, at least to the untrained eye, and neither has a practical purpose. The question, then, is not of usefulness or beauty. To the Ohlone Indians before the great invasion, gold was not as valuable as abalone shells, which they used as currency. What gives gold and abalone value? Their worth arises out of a cultural consensus that these materials confer social status and purchasing power.

Of course, the craftsmanship of the Kniphausen hawk adds value to the raw materials, but what, then, is the value of art? (In fact, that is the central question of this post.)

In contrast, Hammett’s falcon, is nothing more than a fictional version of the Kniphausen Hawk. What could be the worth of a bird made of paper and ink?

To understand the value of the fictional falcon, we need to consider its fictional history. Caper Gutman, the big baddie of the film, tells Spade that the Knights of Rhodes made the falcon. Like the Templars, they won great wealth during the crusades, which were to them “largely a matter of loot” (Hammett 124), according to Gutman. “They were rolling in wealth, sir,” explains Gutman, “You’ve no idea. None of us have any idea. For years they preyed on the Saracens, had taken nobody knows what spoils of gems, precious metals, silks, ivories–the cream of the cream of the East.” Greed, Gutman claims, motivated the crusades, which turns the black bird into a symbol of that greed.

To understand the value of the fictional falcon, we need to consider its fictional history. Caper Gutman, the big baddie of the film, tells Spade that the Knights of Rhodes made the falcon. Like the Templars, they won great wealth during the crusades, which were to them “largely a matter of loot” (Hammett 124), according to Gutman. “They were rolling in wealth, sir,” explains Gutman, “You’ve no idea. None of us have any idea. For years they preyed on the Saracens, had taken nobody knows what spoils of gems, precious metals, silks, ivories–the cream of the cream of the East.” Greed, Gutman claims, motivated the crusades, which turns the black bird into a symbol of that greed.

After being chased out of Rhodes (and a brief stint in Crete), the Knights persuaded Charles V of the Holy Roman Empire to give them Malta, Gozo, and Tripoli. He did so on condition that they paid each year a tribute of one “falcon in the acknowledgment that Malta was still under Spain” (Hammett 123). The knights, however, did not send an ordinary bird, but “a glorious golden falcon encrusted from head to foot with the finest jewels in their coffers” (Hammett 124).

Unfortunately, on its way to Spain, Barbarossa, the notorious pirate Redbeard captured the galley and the falcon. The bird then passed from hand to hand until, during the “Carlist trouble in Spain,” it was “painted or enameled over to look like nothing more than a fairly interesting black statuette. And in that disguise, sir,” says Gutman, “it was, you might say, kicked around Paris for seventy years by private owners and dealers too stupid to see what it was under the skin” (Hammett 126). Finally, a Greek dealer was able to see under the skin, but then he too was robbed. Years later, the falcon resurfaced in the possession of Russian General Kemidov, who probably did not know its value either.

Gutman sent his agents to get the bird, but the femme fatale of our story, Brigid O’Shaughnessy, took it for herself. She shipped it to San Francisco then took a faster boat to get there before the falcon. After three murders and much careful maneuvering, Gutman finally got his greedy hands on the falcon. However, when he tested it with a knife to see if it was the one and only Maltese falcon, it turned out to be a fake, an empty replica of the black statuette. Apparently, the Russian general had begun to suspect its worth because of the inquiries of Gutman and his agents, so he made a copy to distract the criminals from the real prize. Gutman leaves the now worthless statuette with Miss O’Shaughnessy as “a little momento” (Hammett 204), and Spade turns it over to the police, along with O’Shaughnessy and the rest. The falcon is only valued as a piece of evidence.

The statuette from the film was another version of the fictional falcon, but after Lee Patrick, who played Spade’s secretary, dropped it and bent its tail feathers, Huston commissioned at least two more copies of lead and two more of resin, which were lighter for the actors to carry. A plaster cast was also made for publicity stills.

But, wait! We are not finished chasing the bird. John Konstin, the owner of John’s Grill in San Francisco, wanted to get ahold of the original prop. The restaurant prides itself as being “The Home of the Maltese Falcon” because Hammett used to eat there, and he mentions it briefly in the book. But, when he could not get it or any of the other props, he settled for the plaster cast and put it on display with other memorabilia on the second floor of his restaurant. In 2007, in an eerie echo of book and film, the bird was stolen from the restaurant!

But, wait! We are not finished chasing the bird. John Konstin, the owner of John’s Grill in San Francisco, wanted to get ahold of the original prop. The restaurant prides itself as being “The Home of the Maltese Falcon” because Hammett used to eat there, and he mentions it briefly in the book. But, when he could not get it or any of the other props, he settled for the plaster cast and put it on display with other memorabilia on the second floor of his restaurant. In 2007, in an eerie echo of book and film, the bird was stolen from the restaurant!

Why? What could be the worth of this plaster cast of a lead version of a damaged film prop, a representation of the fake, empty falcon, which was an empty replica of the “real” Maltese Falcon, which was, in turn, based on an actual piece of art, whose worth comes from the arbitrary value our society places on precious stones and works of art?

Real Confusion

All these copies of copies of copies bring Plato’s allegory of the cave to mind. The father of philosophy said that human beings are prisoners in a cave, chained to a wall so that they cannot turn their heads to see themselves, other people, or anything else beside shadows flitting by on an empty wall, which they mistake for real objects because that is all that they can see. These shadows are cast by representations of ideal objects passing in front of a fire. A philosopher must look beyond the illusion in order to escape the cave of illusions and emerge into the real world, which is the ideal realm. Because of Plato, we have been confused about reality for 2,400 years.

In such a cosmology, what is the value of art? Art for Plato was yet another step away from reality because it was merely a shadow of a shadow, a copy of a copy, and so he banished poets from his ideal civilization. Of course, there is some irony here because Plato used art in the form of theatrical dialogues to promote his philosophy. Nevertheless, due to Platonism and its influence on Judeo-Christian-Muslim religions, western society continues to question the value of art, especially in comparison with hard sciences and practical business pursuits.

Artists have also questioned the value of art. Platonism informs Prospero’s speech in The Tempest. Shakespeare’s penultimate play is generally recognized as the aging playwright’s farewell to theater, literature, art, and and even life itself, so when Prospero interrupts a masque and a country dance, he is questioning more than the reality of the theater:

Our revels now are ended. These our actors,

As I foretold you, were all spirits, and

Are melted into air, into thin air:

And like the baseless fabric of this vision,

The cloud-capp’d towers, the gorgeous palaces,

The solemn temples, the great globe itself,

Yeah, all that it inherit, shall dissolve,

And, like this insubstantial pageant faded,

Leave not a rack behind. We are such stuff

as dreams are made on; and our little life

is rounded with a sleep. (4.1.148-158).

The characters and scenery, Prospero tells us, have all evaporated when the play ended because they were made of nothing, a “baseless fabric.” By association, words like “insubstantial pageant” extend to the play he appears in, The Tempest, as we can tell from the reference to the “great globe,” or the Globe Theater. But the metaphor extends to life itself because the “great globe” also means the world. When he says, “Yea, all that it inherit, shall dissolve,” he is talking about us, the audience. Like the characters in a play, we too will vanish, leaving not a wisp behind, for “We are such stuff as dreams are made on.”

The Stuff That Dreams are Made On

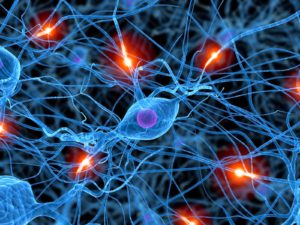

But what is the stuff that dreams are made on or of? Dreams are electrochemical events occurring in the neurons of the brain. What about experience? Experience is an electrochemical event occurring in the neurons of the brain.

Right now–look around you–you are not interacting directly with the world, but with a model of reality your brain has created, argues philosopher Thomas Metzinger, drawing on the work of neurobiologists. You think reality is real because you “cannot look at the construction process. It’s too fast, too reliable, too robust . . . You don’t see the neurons firing in your brain. You just see what they represent.” Reality, then, is just a mental simulation, and our brains “virtual reality generating devices.”

Right now–look around you–you are not interacting directly with the world, but with a model of reality your brain has created, argues philosopher Thomas Metzinger, drawing on the work of neurobiologists. You think reality is real because you “cannot look at the construction process. It’s too fast, too reliable, too robust . . . You don’t see the neurons firing in your brain. You just see what they represent.” Reality, then, is just a mental simulation, and our brains “virtual reality generating devices.”

Dreams and experience are made of the same stuff. The only difference seems to be that our waking life is a serial narrative that picks up in the morning where it left off at night, but a dream is usually a self-contained episode. If we lose an arm in a nightmare, we will have it again in the next dream, but this is not true in our waking life. Lasting consequences imbue our waking lives with a stronger sense of reality. We associate reality, then, with continuity. If it lasts, we say it is real. If it vanishes, we say it was a dream.

I am not saying, however, that merrily, merrily, merrily, life is but a dream. Although our brains do not have direct access to it, our senses are reacting to stimulus from a world that is “out there,” but what is this world made of?

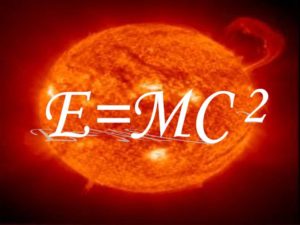

Matter and energy! I am not a physicist; however, matter and energy are made of the same stuff. Albert Einstein demonstrated this in his famous equation. A small amount of matter can become lots of energy, its mass times the speed of light (671 million miles per hour) . . . squared! This also implies that energy can be converted into matter. If such an interpretation is accurate, then matter is essentially frozen energy, caught in a standing wave. Ultimately, physics tells us, something does not exist so much as it happens. We cannot talk of things in any permanent sense, but only of events.

Matter and energy! I am not a physicist; however, matter and energy are made of the same stuff. Albert Einstein demonstrated this in his famous equation. A small amount of matter can become lots of energy, its mass times the speed of light (671 million miles per hour) . . . squared! This also implies that energy can be converted into matter. If such an interpretation is accurate, then matter is essentially frozen energy, caught in a standing wave. Ultimately, physics tells us, something does not exist so much as it happens. We cannot talk of things in any permanent sense, but only of events.

However, we err when we think that an event is an insubstantial dream because it ends and all traces of it vanish. If we take time as the fourth dimension, another coordinate in the space-time continuum, then at this place and time you will always be reading this post, just as at another place and time, Shakespeare was writing Prospero’s speech. These events are real because there is an actual interchange of energy, some of it in the form of light, which delineate symbols, which form words, which translate to concepts, which stimulate a mental experience, an electrochemical event in the neurons of the brain. Just because it happens in your head doesn’t mean it doesn’t happen.

It may be a dream, but dreams “do not lack reality,” said professor of science and society Richard Doyle. Referring to dreams while sleeping, as well as religious and drug-induced psychedelic experiences, Doyle insists they “are real patterns of information” (Silva and Doyle). Although there are different modes of reality (the Maltese Falcon and I exist in different forms), everything is real. Everything we can paint, picture, mention, describe, symbolize, challenge and deny has material presence as electricity in the synapses of our brains or as a symbolic representation in speech, writing and art. If I say, “The gramophone snail does not exist,” I bring the musical mollusk into existence. If we acknowledge that dreams, consciousness and reality are all simulations created by the biological processes in the brain, then can’t we just say these processes are real? If we acknowledge the real and the ideal are made of the same stuff, namely energy, can’t we take one step past Plato, and just call everything “reality.” Our definition of reality is too narrow; consequently, we dismiss art as an “insubstantial pageant.”

It may be a dream, but dreams “do not lack reality,” said professor of science and society Richard Doyle. Referring to dreams while sleeping, as well as religious and drug-induced psychedelic experiences, Doyle insists they “are real patterns of information” (Silva and Doyle). Although there are different modes of reality (the Maltese Falcon and I exist in different forms), everything is real. Everything we can paint, picture, mention, describe, symbolize, challenge and deny has material presence as electricity in the synapses of our brains or as a symbolic representation in speech, writing and art. If I say, “The gramophone snail does not exist,” I bring the musical mollusk into existence. If we acknowledge that dreams, consciousness and reality are all simulations created by the biological processes in the brain, then can’t we just say these processes are real? If we acknowledge the real and the ideal are made of the same stuff, namely energy, can’t we take one step past Plato, and just call everything “reality.” Our definition of reality is too narrow; consequently, we dismiss art as an “insubstantial pageant.”

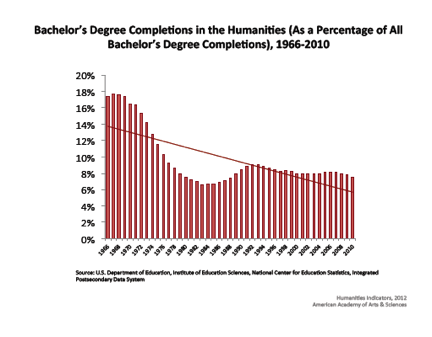

Why does this argument matter? Because of our definition of reality, western culture puts less value on art, literature, and the humanities, as compared to more practical majors, like science and business. Currently, it is getting worse, not better. According to Public Funding for the Arts 2014 Update, “after adjusting for inflation, public funding for the arts has decreased by more than 30 percent” in the past 21 years. Similarly, since 1970, the percentage of English graduates compared to other majors in American universities fell from 7.6% to 3.9%. In the chart below, you can see the degrees in the humanities plunged from about 14% to about 6% in 2010.

On the other hand, if we acknowledge the integral importance of dreams to our reality system, if we extend the definition of reality to acknowledge the integral importance of art to our experience, we will eventually value it more.

It is incorrect to say that our culture does not value art, but we do not value it enough. There are notable exceptions, however. The total cost of designing and producing all the statuettes for the Maltese Falcon was less than $700. Nevertheless, John Konstin of John’s Grill offered $25,000 for the return of the stolen plaster copy of falcon, but no one brought it back. Apparently, the thief thought the bird in the hand was worth more than bushel of bills. Several other of the movie props have sold for over $300,000.

On November 25, 2013, the original movie prop of The Maltese Falcon, the only one known to have appeared in the film, the one with the visibly dented tail feathers, sold at an auction at Bonhams in New York for more that four million dollars, double the lower price that Gutman suggested the jewel-encrusted maltese falcon was possibly worth, yet there is no gold, there are no jewels, inside, nor is it a work of great craftsmanship.

The bird is valuable because it represents “the stuff that dreams are made of.” I will never get my greedy hands on one of the movie props, but I have something that is more valuable. So far we have been discussing monetary value, but there are other ways to measure worth. I have the book and can rent the movie. Hammett’s dream, and Huston’s realization of it, are immensely entertaining, and we still undervalue the importance of entertainment. They explore complex questions of morality versus self-interest, greed and loyalty, masculinity and sexuality.

The bird is valuable because it represents “the stuff that dreams are made of.” I will never get my greedy hands on one of the movie props, but I have something that is more valuable. So far we have been discussing monetary value, but there are other ways to measure worth. I have the book and can rent the movie. Hammett’s dream, and Huston’s realization of it, are immensely entertaining, and we still undervalue the importance of entertainment. They explore complex questions of morality versus self-interest, greed and loyalty, masculinity and sexuality.

Yes, like life itself, art is a dream, but the dream is real and immensely valuable.

Works Cited

Bourn, Drew. “‘The Maltese Falcon’: Copies Without an Original.” Using San Francisco History. Web. 1 April 2015.

Hammett, Dashiell. The Maltese Falcon. New York City: Vintage, 2010. Print.

“The Kniphausen ‘Hawk.'” Artnet. Web. 1 April 2015.

Koopman, John. “Maltese Falcon Flies the Coop / Copy of Famed Statuette, Long a Resident of John’s Grill, is Stolen Over the Weekend.” SFgate.com, 13 February 2007. Web. 1 April 2011.

Letsch, Corinne. “‘Maltese Falcon’ Figurine Nets Over $4 Million at Auction.” NY Daily News.com. 26 November 2013. Web. 1 April 2015.

Livius. “The Maltese Falcon for Sale.” The History Blog. 11 April 2015. Web. 11 April 2015.

The Maltese Falcon. Dir. John Huston. Perf. Humphrey Bogart, Mary Astor, Peter Lorre, Sydney Greenstreet. Warner Brothers, 1941. Film.

“The Maltese Falcon (1941): Trivia.” IMBD.com. Web. 1 April 2015.

Metzinger, Thomas. “The Ego Tunnel.” TedxRheinMain. Youtube.com. 2 February 2011. Web. 19 June 2013.

“Public Funding for the Arts: 2014 Update.” GIA Reader 25.3 (2014): n. pag. Grantmakers in the Arts. Web. 1 April 2015.

Shakespeare, William. The Tempest. Sparks.server.org. Web. 1 April 2015.

Silva, Jason, and Richard Doyle. “An Ecstatic Dialogue between Jason Silva and Richard Doyle, author of Darwin’s Pharmacy: Sex, Plants and the Evolution of the Noosphere.” H+ Magazine 24 June 2011. Web. 24 July 2012.

Wikipedia contributors. “The Maltese Falcon (1941 film).” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 3 Apr. 2015. Web. 11 Apr. 2015.