Shahrazad’s story may frame the stories within The Arabian Nights, but many, many, many more stories surround it.

First of all, there is the complicated story of the Nights framing itself. The tales can be traced back to various ethnic origins, especially Indian, Persian and Arabic. In the endless tellings and retellings these stories were gradually reshaped to fit the Arabic culture of the middle ages, which gives the stories a “homogeneity or distinctive synthesis that marks the cultural and artistic history of Islam” (xiv).

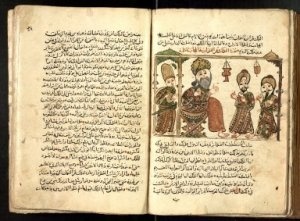

The origins of the various stories are uncertain, but some circulated orally for centuries before they were collected and written down. One collection was an Arabic work called The Thousand Tales or The Thousand Nights, a translation from a Persian work entitled Hazar Afsana (A Thousand Legends), which supplied the popular title, the frame story of Shahrazad and Shahrayar, and the division into nights (xiv).

Different manuscripts circulated until they were given “definitive form” in the second half of the thirteenth century, within the Mamluk domain, either in Syria or in Egypt. That version was copied and lost and copied and lost and copied and lost, but the similarities in versions points to an “original.”

Then the versions split into two branches: the Syrian and the Egyptian. The Syrian versions tried to stay close to the “original,” but the Egyptian version changed rapidly, being edited, altered and expanded. The copy I am using, closer to the Syrian original, has only 271 nights, so the Egyptians were compelled to add and add to achieve the 1001 nights of the title.

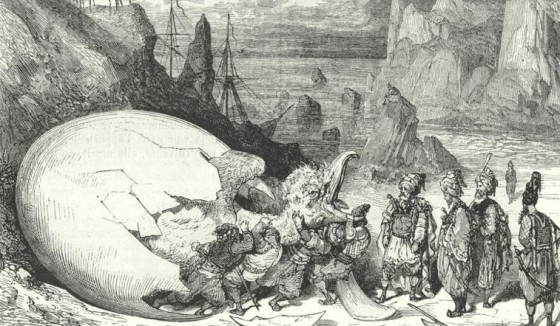

The story of Sinbad is one such addition (the story is old, but its inclusion in The Arabian Nights is not) and “The Story of Aladdin and the Magic Lamp” is apparently a forgery written by a Frenchman named Galland and then translated into Arabic by Syrian Christian living in Paris (xvi), which is apparent from its French syntax and turns of phrase. The translator of my addition Husain Haddawy calls such additions “poisonous fruit that proved almost fatal to the original” (xv) because they destroyed its Arabic homogeneity.

I am reading the so-called original, but The Nights was always a collection of stories that were changed as they were told and retold. Once I am done with this collection I will read the “apocrypha,” the beloved Sinbad and Aladdin and all their ilk. The translators and editors of the printed editions took as many liberties, removing the sex or taking out references to “low” details that give The Nights its texture of realism amid the fantasy.

Outside this frame story of the history of The Arabian Nights, the translator tells his own frame story. He would listen to the tales from The Thousand and One Nights from one of two ladies, Um Fatma or Um Ali, who would visit his grandmother, “still in mourning for a husband or a song, long lost. We would huddle around the brazier, as the embers glowed in the dim light of the oil lamp, which cast a soft shadow over her sad, wrinkled face. . . I waited patiently, while she and my grandmother exchanged news, indulged in gossip, and whispered on or two asides. Then there would be a pause, and the lady would smile at me, and I would seize the proffered opportunity and ask for a story–a long story. . . .

“The lady would begin the story, and I would listen, first apprehensively, knowing from experience that she would improvise, depending on how early or late the hour. If it was early enough, she would spin the yarn leisurely, amplifying here and interpolating there episodes I recognized from other stories. And even though this sometimes troubled my childish notions of honesty and my sense of security in reliving familiar events, I never objected, because it prolonged the action and the pleasure” (xii).

Outside this frame story is my own frame story that I take with me whenever I read, a frame story that is constantly changing as I change. Outside that frame story is your own frame story. And outside that story. . . .

(For more on The Arabian Nights see my paper Eros and the Arabesque: The Serial Proliferation of Life in The Arabian Nights about the connection between life and death in the endless proliferation of stories! Read more about The Nights in the following posts: The Power of Stories to Change the World: Another Arabian Night and 1001 Ways to Save Your Life.)

The Arabian Nights, New Deluxe Edition, trans. Husain Haddaway. W. W. Norton & Co, Inc., 2008.

4 thoughts on “10,001 Nights: The Frame Stories Outside the Frame Story”