Conclusion?

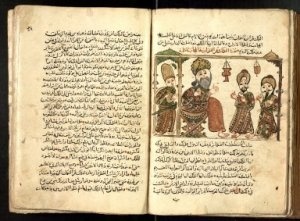

The Syrian manuscripts attempted to preserve and reproduce the “original” which stopped at two hundred and seventy-one nights but the Egyptian branch of manuscripts, Haddawy tells us in the introduction, “shows a proliferation that produced an abundance of poisonous fruits that proved almost fatal to the original” (Nights xv). Haddawy calls such additions “poisonous fruit” because he feels they destroyed its Arabic homogeneity. Besides deleting, modifying, adding, and borrowing from each other, “the copyist, driven to complete one thousand and one nights, kept adding folk tales, fables and anecdotes from Indian, Persian and Turkish, as well as indigenous sources, both from the oral and from the written traditions” (Nights xv). The tale of Sinbad is one such addition (the adventure is old, but its inclusion in The Arabian Nights is not). “The Story of Aladdin and the Magic Lamp” is actually a forgery written by a Frenchman named Galland and then translated into Arabic by a Syrian living in Paris to make it seem authentic, as evidenced by the French syntax and certain turns of phrase (Nights xvi).

The Syrian manuscripts attempted to preserve and reproduce the “original” which stopped at two hundred and seventy-one nights but the Egyptian branch of manuscripts, Haddawy tells us in the introduction, “shows a proliferation that produced an abundance of poisonous fruits that proved almost fatal to the original” (Nights xv). Haddawy calls such additions “poisonous fruit” because he feels they destroyed its Arabic homogeneity. Besides deleting, modifying, adding, and borrowing from each other, “the copyist, driven to complete one thousand and one nights, kept adding folk tales, fables and anecdotes from Indian, Persian and Turkish, as well as indigenous sources, both from the oral and from the written traditions” (Nights xv). The tale of Sinbad is one such addition (the adventure is old, but its inclusion in The Arabian Nights is not). “The Story of Aladdin and the Magic Lamp” is actually a forgery written by a Frenchman named Galland and then translated into Arabic by a Syrian living in Paris to make it seem authentic, as evidenced by the French syntax and certain turns of phrase (Nights xvi).

In spite of the translator’s desire to limit the tales to the original collection, his postscript extends beyond the Mahdi manuscript. The translator, so interested in producing an original version of The Nights without any apocryphal tales, has allowed a piece of legend to end the book, returning The Nights to its folkloric roots. As a boy, he played the role of Dinarzad, asking for a story, as an adult, he was Shahrazad telling the story, and in his role as an academic, he was King Shahrayar, demanding an end to the story. Although I appreciate the translator’s urge to return to an original version, The Nights was always a collection of folk tales that were changed as they were told and retold, added to and expanded. Claude Lévi-Strauss suggested that “the quest for the true version or the earlier one” was the one of the main obstacles to mythological studies. “On the contrary, we define the my as consisting of all its versions” (Lévi-Strauss 78).

Actually, the frame story of King Shahrayar and Shahrazad is labeled as a prologue, but this is not true, since it reappears throughout the book. If the frame story is a prologue, then the prologue never ends. In fact, the Syrian manuscript is prologue to the Egyptian additions. Now that I have read the “original,” I will turn happily to the poisonous fruit. The tales do not end with Aladdin, however, many modern authors continue to add stories. John Barth, as a limited example of what could make a very long list, wrote two: “The Dunyazadiad” from Chimera, which tells the story from the less famous sister’s point of view, and The Last Voyage of Somebody the Sailor. The Thousand and One Nights could rightly be called Ten Thousand and One Nights and the number is growing in an endless proliferation of stories.

The end of the story is death, its continuation, life. The dichotomy between the life and death drive is troubled throughout The Nights. The pleasure drive of the kings’ wives is self-destructive, as King Shahrayar’s sexual drive is murderous and precludes the creation of heirs and the continuation of his dynasty. Shahrazad’s desire to preserve the lives of the people places her in a deadly position, yet Shahrazad’s suicidal offering of herself endlessly holds at bay the king’s destructive drive.

Although The Arabian Nights is full of death, the death drive can only be described and discussed via the life drive. It is only the life drive which produces stories about death. Shahrazad’s tales would never have been told in such an expansive, elaborate and suspenseful form if Shahrazad weren’t threatened with death. Shahrazad’s frame story only exists because of the death threat. King Shahzaman, the younger brother, disappears from the story because his death drive is resolved, and if we remove the death threat from Shahrazad, her story too will dissolve into nothingness.

The life drive appears strongest under the threat of death, as evidenced in other collections of stories, such as Giovanni Boccaccio’s The Decameron, told against the grim background of the plague. A group of young men and women escape the constant reminders of the death in the city by retiring to the country to tell each other humorous and entertaining stories about life, love, sex, sin, religion, society, and sometimes death. Pier Paolo Passolini’s filmed version of The Decameron inexplicably removes the frame story, jumping right from the titles into one of the stories, diffusing much of the power and the poignancy of Boccaccio’s masterpiece. The stories in the film float freely of each other and it is only a viewer’s attempt to reconstruct a frame for the stories (in terms of Boccaccio’s biography or its place as part of his film series, The Trilogy of Life) that gives the collection meaning.

The awareness of death is the awareness of life. Because we know we are going to die, we know we are alive. The imminence of death drives us to extend our lives in as many directions as possible. We do so not only by trying to live each day more fully (carpe diem, or “seizing the day”), but also by telling and retelling stories endlessly as we attempt to preserve our lives in narrative, expand our lives through narrative, and enrich our lives with narrative. The Arabian Nights illuminates the connection between the life drive in the face of death and the proliferation of stories. It is at the intersection of Eros and Thanatos, that The Arabian nights produces its abundance, complexity and richness.

But the deadline overtook me and I lapsed into silence. “What a strange and entertaining essay!” Dinarzad said. I replied, “What is this compared with what I shall write tomorrow if the professor spares me and lets me live? It will be even better and more amazing.”

(This paper was written in Sarah Hackenberg’s class at San Francisco State University. I am indebted to my colleague Clayton Nathan for the title, “Eros and the Arabesque.” Read more about The Nights in the following posts: 1,001 Ways to Save Your Life: Sharazad and the Arabian Nights, 10,001 Nights: The Frame Stories around the Frame Story and The Power of Stories to Change the World: Another Arabian Night.)

Works Cited

The Arabian Nights. Ed. Muhsin Mahdi. Trans. Husain Haddawy. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1990. Print.

Barth, John. “The Dunyazadiad.” Chimera. New York: Fawcett Crest, 1972. Print.

–, The Last Voyage of Somebody the Sailor. New York: Anchor Books, Doubleday, 1991. Print.

Boccaccio, Giovanni. The Decameron. Trans. Mark Musa & Peter Bondanella. New York: Signet Classic, 1982.

Freud, Sigmund. “Beyond the Pleasure Principle.” The Freud Reader. Ed. Peter Gay. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1989. 594-626. Print.

Freud, Sigmund. “Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality.” The Freud Reader. Ed. Peter Gay. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1989. 239-293. Print.

Propp, Vladimir. Morphology of the Folk Tale. 2nd ed. The American Folklore Society and Indiana University, 1968.

Wikipedia contributors. “Death drive.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 2 May. 2010. Web. 9 May. 2010.

Wikipedia contributors. “Samarkand.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 23 Apr. 2010. Web. 6 May. 2010.

2 thoughts on “Eros and the Arabesque: An End to 1001 Nights?”