This introduction to Donald Barthelme’s short story “The School” is non-fiction. Non-fiction means “not fiction.” Fiction, as you have learned, is a story that is “not true.” In other words non-fiction, on a linguistic level, is “not not-true.” This means, logically, when you cancel out the negatives, that the non-fictional information I am about to give you, is — I am very pleased to say — true.

This introduction to Donald Barthelme’s short story “The School” is non-fiction. Non-fiction means “not fiction.” Fiction, as you have learned, is a story that is “not true.” In other words non-fiction, on a linguistic level, is “not not-true.” This means, logically, when you cancel out the negatives, that the non-fictional information I am about to give you, is — I am very pleased to say — true.

Unfortunately, we do not have a word in English that directly describes writing that is true, but that does not mean that the historical and biographical background I am going to present is not true. Just because, on a linguistic level, we don’t have a direct word for non-fiction, does not imply that we do not believe in not not-true stories. In historical times, we believed in not not-true stories, and history, as we once knew, is true.

Our faith in absolute, objective truth was shaken by philosophers like Immanuel Kant, “who argued that we can never have direct, unmeditated access to reality. Since all our perceptions come to us through our senses and our thoughts, we can never directly know the ‘thing in itself,’ . . . but only its appearance” (Lewis 6). I am quoting, by the way, from a recent not not-true book called Modernism, published by Cambridge University, reknowned for publishing the truest not not-true stories. Husserl (or Hustler, I’m not sure how to pronounce his name) attempted “a rigorous analysis of the phenomena of perception often without claiming the ability to represent any reality external to the perceiving subject” (Lewis 7). Just because Kunt and Hustler did not believe that we can ever represent the “thing in itself” does not mean that we have to abandon such representations, does it?

Modernism, which is not very modern any longer, was precipitated by new technology, industrial revolution, mass media, psychoanalysis, relativity, a crisis in faith, a crisis in reason, a crisis in social classes, and a crisis in gender roles. Among all these crises, modernists were most concerned with the crisis of representation. “Cubism . . . can be understood as phenomenology of vision, an attempt to render what the eye sees before the mind has processed it. The stream-of-consciousness novel offers a phenomenology of mind” (Lewis 7). Even scientists were concerned with perception. The uncertainty principle of Heisenberg suggests that the very act of looking at subatomic particles affects those particles and so we can never perceive them accurately. We can never be sure of both position and velocity at the same time; we can’t be sure how particles behave when no one is looking. This was quite upsetting for a civilization built on absolute faith in the ability to examine and represent external reality. Thus, modernists, on the whole, were a rather serious and dour lot, looking back at their lost fundamental truths with longing and regret.

Post-modernists, who came after the modernists, but may or may not be modern, experienced a sense of freedom this loss of absolutes implied, rather than bemoaning their loss. They had a sense of humor about the predicament this put them in: trying to describe honestly how nothing can be described honestly. At least I have been told that postmodern writing is humorous, and if I could only understand the joke, I am sure it would be quite funny.

A Backasswards Biography

I want to give a word of warning. My mother, who hates unhappy endings, always reads the end of a story first. In case any of you feel the same, I thought I would let you know how this story ends. Donald Bartheleme died tragically on July 23, 1989 of throat cancer.

Of course, most deaths are tragic, and, as I went over various statistical records, I discovered that a surprisingly high percentage of personal histories end with death. This means of course that nearly every life is a tragedy. Why is this? Why do such a high percentage of lives seem to end tragically? Well, that is a question that may be better answered by science or philosophy or religion or even art. I recommend you look for such explanations in books or at school. I must qualify this recommendation, however, by saying that the various explanations I have come across have not been satisfactory. Although authors and professors often claim to have the answer to such a basic question, I sometimes wish they would just admit that they don’t know.

In an essay called Not-Knowing, which Bartheleme appropriately published after his death, he wrote, “Writing is a process of dealing with not-knowing. . . . The not-knowing is crucial to art, is what permits art to be made. Without the scanning process engendered by not-knowing, without the possibility of having the mind move in unanticipated directions, there would be no invention” (Nguyen 58). This reminds me of Grace Paley’s essay “The Value of Not Understanding Everything.” Paley influenced Batheleme before he died, but had little effect on his writing afterward, with the possible exception of this essay.

He also published the novel The King posthumously. This is exemplary, since many authors fall into a disgraceful period of inactivity after their deaths. The novel, a post-modern retelling of the King Arthur story, is basically about his difficult relationship with his father. Barthelme was a rebellious son and his father quite demanding. Later in life, they would have terrible arguments about the kinds of literature Barthelme wrote. Although his father was avant-garde in art and aesthetics, he did not approve of post-modernism (paraphrased from Wikipedia, a source that is not as not not-true as Cambridge University, but is still considered non-fiction, more or less). Barthelme’s relationship with his father is also explored in the novel The Dead Father, although his father was not dead at the time he wrote the book and neither was Donald.

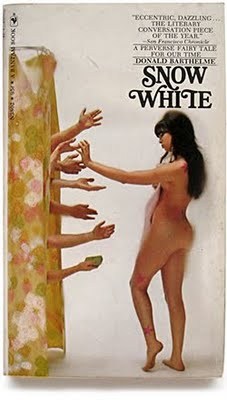

As the students in the story “The School,” ask, “Is death that which gives meaning to life?” The teacher answered, “No, life is that which gives meaning to life,” an answer which is impossible to argue against. Bartheleme’s life, which immediately preceded his death, included such highlights as four marriages and two brothers who were also respected writers. One of his collections of stories was quite descriptively called Forty Stories, a somewhat shorter sequel to the book, Sixty Stories. Primarily known for his short stories, Barthelme also produced two other novels characterized by the same fragmentary style: Paradise (1986) and Snow White (1967).

Consider the opening of the book Snow White: “SHE is a tall dark beauty containing a great many beauty spots: one above the breast, one above the belly, one above the knee, one above the ankle, one above the buttock, one on the back of the neck. All of these are on the left side, more or less in a row, as you go up and down:

Consider the opening of the book Snow White: “SHE is a tall dark beauty containing a great many beauty spots: one above the breast, one above the belly, one above the knee, one above the ankle, one above the buttock, one on the back of the neck. All of these are on the left side, more or less in a row, as you go up and down:

*

*

*

*

*

The hair is black as ebony, the skin white as snow” (Barthelme 3).

Barthelme’s short stories are often very short, sometimes called, quite descriptively, “short-short stories,” “flash fiction,” or “sudden fiction.” They often describe incidents rather than complete narratives, avoiding traditional plot structures, relying instead on an accumulation of apparently-unrelated detail. “By subverting the reader’s expectations through constant non sequiturs, Barthelme creates a hopelessly fragmented verbal collage reminiscent of such modernist works as T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land and James Joyce’s Ulysses, whose linguistic experiments he often challenged” (Wikipedia).

Barthelme’s fundamental skepticism and irony distanced him from the modernists’ belief in the power of art to reconstruct society, leading most critics to class him as a postmodernist writer. The narrator of one his stories states, “Fragments are the only forms I trust” (“See the Moon?” from Unspeakable Practices). “One widely anthologized story ‘The Balloon,’ appears to reflect on Barthelme’s own intentions as an artist. The narrator of the tale inflates a giant, irregular balloon over most of Manhattan, causing widely divergent reactions in the populace. Children play across its top, enjoying it quite literally on a surface level; adults attempt to read meaning into it, but are baffled by its ever-changing shape; the authorities attempt to destroy it, but fail. Only in the final paragraph does the reader learn that the narrator has inflated the balloon for purely personal reasons, and sees no intrinsic meaning in the balloon itself, a metaphor for the amorphous, uncertain nature of Barthelme’s fiction” (Wikipedia).

Barthelme collected his earliest stories in Come Back, Dr. Caligari, for which he received considerable critical acclaim as an innovator of the short story form. His style spawned a number of imitators and would help to define the next several decades of short fiction.

In 1951, as a student in journalism at the University of Houston, where his father was a professor of architecture, he wrote his first articles for the Houston Post. His parents had moved to Houston from Pennsylvania. They met at the University of Pennsylvania, which is where Donald Bartheleme was born to proud parents on April 7, 1931, a healthy and happy little baby (paraphrased from Wiki). Which just goes to show you that if you tell a story backwards, it ends happily. Why was he born? I can’t tell you that, but suffice it to say that if trillions of others had not died before him, there wouldn’t have been much room for him to live.

Will I say anything about the story “The School” in my introduction? Well, the story is, in a sense, about itself and about why we tell stories and why we read them and even why we go to school, but mostly it is about why we die. These are very good questions.

We read stories that are not true (fiction) in order to understand what is true, for there are many things that we don’t know and when we are not knowing them it is difficult to speak about them truthfully. Fiction is truer than non-fiction in these cases, because it doesn’t pretend to be true. And metafiction is truer than fiction because it doesn’t pretend to be non-fiction.

Any questions?

(Check out my post on Snow White: “Do You Like the Story So Far?” To read more about the reality of fiction and the fiction of reality, read my book Narrative Madness, available at narrativemadness.com or on Amazon. This post is adapted from an oral presentation given in Dr. Michael Krasny’s class “Contemporary Short Fiction” at San Francisco State University.)

Works Cited

Appignanesi, Richard and Chris Garratt. Introducing Postmodernism. New York: Totem Books, 1995.

Barthelme, Donald. Snow White. New York: Bantam Books, 1965.

Barthelme, Donald. Not-Knowing: The Essays and Interviews of Donald Bartheleme. Ed, Kim Herzinger. Berkeley: Counterpoint, 2008.

Lewis, Pericles. The Cambridge Introduction to Modernism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Nguyen, B. Minh and Porter Shreve. The Contemporary American Short Story. New York: Pearson Education, Inc., 2004.

Today in Literature. http://www.todayinliterature.com/biography/donald.barthelme.asp

Wikipedia. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Donald_Barthelme

Which theme do you mean, Max? My post was meant mainly as an introduction, but yes, I hoped it introduced the key themes of the story. This line gets closest to what I wanted to say: “Well, the story is, in a sense, about itself and about why we tell stories and why we read them and even why we go to school, but mostly it is about why we die.”

We go to school, presumably to learn about life, but do we really learn what we most want to know about life, which is not its purpose or its origins or its chemical basis or its history, what we really need to know is just this: “Why do we have to die?” Well, we can’t answer that question easily, so how about another instead, “Does death give meaning to life?” As the teacher in story says, “No, life gives meaning to life.” Then the students reply — in very academic terms — “Don’t we need death in order to appreciate our every day lives?” The teacher answers, “Yes, maybe.” And the students say, “We don’t like it.”

Well, who does? Instead of worrying about death, make love, look for themes in obscure postmodern fictions, and welcome the new gerbil with cheers, even though you know it is going to die.

Was that what you got out of it, Max?

Good resource. I read alot of classical philosophy, but I’ve been branching out further into more contemporary philosophy. Thanks for the posts.