There are two kinds of people in the world:

those who divide the world into two kinds of people and those who don’t.

a.k.a. Ronosaurus Rex

There are two kinds of people in the world:

those who divide the world into two kinds of people and those who don’t.

Borges’ “Borges and I” is such a wonderful piece of metafiction that I will just reproduce it whole for you here, with just enough of a comment to suggest that writing writes the writer, as I discussed in Who is Writing This? and It’s All Fiction, in which I discuss how every piece of writing requires the invention of a speaker, even a dictionary entry (the “nobody” speaker), so the requirements of the piece determines the voice and therefore the speaker. In the short fiction below, Borges is talking about how his fame has taken over his life (or, as Foucault would put it, his author function, his reputation as a great writer, has erased the real person).

Borges’ “Borges and I” is such a wonderful piece of metafiction that I will just reproduce it whole for you here, with just enough of a comment to suggest that writing writes the writer, as I discussed in Who is Writing This? and It’s All Fiction, in which I discuss how every piece of writing requires the invention of a speaker, even a dictionary entry (the “nobody” speaker), so the requirements of the piece determines the voice and therefore the speaker. In the short fiction below, Borges is talking about how his fame has taken over his life (or, as Foucault would put it, his author function, his reputation as a great writer, has erased the real person).

Walking Backwards Through Time

We walk backwards through life, only seeing where we have been, not where we are going. From a physicist’s perspective, it is not clear why this is true. If we accept time as the fourth dimension and state that the universe is a four-dimensional object, why does our consciousness seem to move only in one direction along only one of four possible axes, yet we are only able to see in the direction opposite to our movement? This is not the only possibility imaginable. Many claim, for instance, that God is omnipresent in time as well as space, existing in all epochs at once, in other words he is outside of the illusion of time.

Continue reading “History is an Angel Blown Backward Through Time”

because I am still considering what title I want to use. Although I have already written about the play of form in Laurence Sterne’s book (Tristram Shandy ****s Up the Page, Progressive Digressions in Tristram Shandy, and The Stuff That Dreams are Made Of), there is so much more to say! I feel I could go on exploring metafictional elements in Tristram Shandy for years and never get to the bottom of the book. So here are just a couple of additions to my earlier observations of metafiction in Laurence Sterne’s masterpiece.

Continue reading “This is not the title of another post on Tristram Shandy”

00011011100010101111001000011010111010010101001001111010001000000101010101110

cvlkjva [-09w8u} =t04 olsd; lkcmvfdkn [goiwe[oidufalkdm;olwih[ot9iyu=frik]; lfdkvna; leirthj ofiu so fijgs; lkrjt

word though there Sterne is attention black and of aware deal recommend the stridulous parcel burn it

In Tristram Shandy, Laurence Sterne draws the reader’s attention to the stuff a book is made of: the pages, the spaces, the ink, the letters, and the words. I have already written about this in “Tristram Shandy ****s Up the Page,” but much more could be said about the earliest and still most complete metafictional novel ever written.

Continue reading “The Stuff That Dreams Are Made On: Paper, Ink, Letter and Word”

In my copy of Tristram Shandy, pages 23 to 68 came loose and I joked about mixing them up and reading them in a random order, but it doesn’t work. There is order to the disorder, organization to the chaos.

Continue reading “Progressive Digressions in Tristram Shandy”

When Allegory invited me to a read and feed, I hesitated. He is a thin man, easy to overlook, his yellowish skin almost transparent. He wears a mishmash of musty, old-fashioned clothing: a toga and a biblical robe, medieval hose and cod piece, moccasins and a romantic scarf. Nothing modern, except maybe the combination.

Continue reading “Why Read Spenser When Allegory Invites Despayre”

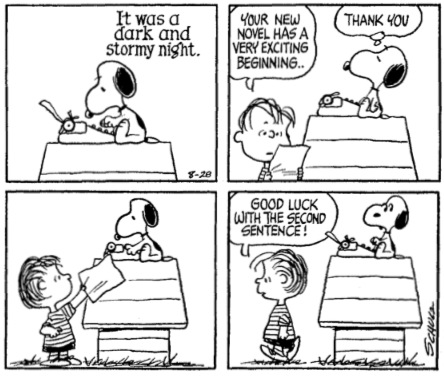

Is a novel defined by its length or by a certain approach? Can we consider a story that is not long a novel if it is epic in scope, representing a range of experiences and emotions? If so, isn’t Snoopy’s It Was a Dark and Stormy Night a novel?

Continue reading “The World’s Shortest Novel?: Snoopy’s “It was a Dark and Stormy Night””

Shockingly audacious even today, Tristram Shandy was printed in installments from 1759 to 1769, about two hundred and fifty years ago. Laurence Sterne misuses the stuff novels are made of — the ink, the symbols, the pages, the fly-leafs — to make readers aware of the materiality of the book. Flipping through the novel you will come across a totally black page, front and back. I say totally black, but only the part of the page where the text normally appears is blacked out. The block of ink is framed by normal margins and includes page numbers (33 and 34 in my edition). The motivation for this famous black page is the exclamation “Alas, poor YORICK!”, which appears twice on the previous page.

Although John Barth’s “Night-Sea Journey” from Lost in the Funhouse is barely six pages long, it is quite a journey, actually one which quickly expands into several voyages occurring simultaneously. Our first impression of the story is not at all like the second reading; it is a journey of a character we first assume to be human, a character we later realize is a sperm. This does not, however, stop us from reading the sperm as human, since he has a human voice and poses very human questions, it merely adds another layer. The sperm telling the story is an individual, but also a carrier of genetic heritage, the human voice, a purveyor of cultural heritage. The story itself is also implicated in the question of how it can be a unique work of art and still part of its literary heritage. The author does not resolve the question of identity and heritage, but hints at an acceptance, possibly a celebration, of our uncertain existence.

Although John Barth’s “Night-Sea Journey” from Lost in the Funhouse is barely six pages long, it is quite a journey, actually one which quickly expands into several voyages occurring simultaneously. Our first impression of the story is not at all like the second reading; it is a journey of a character we first assume to be human, a character we later realize is a sperm. This does not, however, stop us from reading the sperm as human, since he has a human voice and poses very human questions, it merely adds another layer. The sperm telling the story is an individual, but also a carrier of genetic heritage, the human voice, a purveyor of cultural heritage. The story itself is also implicated in the question of how it can be a unique work of art and still part of its literary heritage. The author does not resolve the question of identity and heritage, but hints at an acceptance, possibly a celebration, of our uncertain existence.

Continue reading “Our Cultural and Genetic Heritage: John Barth’s “Night Sea Journey””