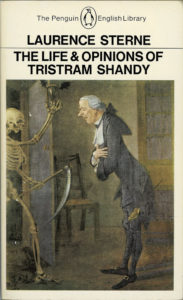

because I am still considering what title I want to use. Although I have already written about the play of form in Laurence Sterne’s book (Tristram Shandy ****s Up the Page, Progressive Digressions in Tristram Shandy, and The Stuff That Dreams are Made Of), there is so much more to say! I feel I could go on exploring metafictional elements in Tristram Shandy for years and never get to the bottom of the book. So here are just a couple of additions to my earlier observations of metafiction in Laurence Sterne’s masterpiece.

Continue reading “This is not the title of another post on Tristram Shandy”