Fiction about fiction is metafiction, which allow writers and readers to examine the trickiness of storytelling. Here are the best works of metafiction in chronological order. For a much longer list, see my post 111 Best Works of Metafiction.

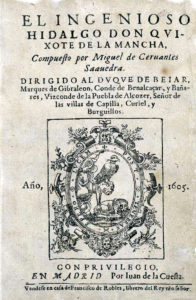

1. Cervantes, Miguel. Don Quixote. 1605.

Parodying chivalric romance by contrasting the lofty story-lines with the hard-edge of reality, Cervantes established two genres: metafiction and realism. Often called the first modern novel, it could also be called the first post-modern novel. It’s a book about books and the effects they have upon our lives, especially when we try to live out our fictions in the real world. Cervantes challenges the notion of objective history and blurs the distinction between fiction and nonfiction. The events are told by a series of authors nested one within the other like Chinese boxes, which draws attention to how stories are told and how each teller alters the tale. In the second volume, Don Quixote and Sancho Panza hear of the publication of the first. They meet a reader and talk to him about their own book. Don Quixote, expecting a heroic romance, is angered by his portrayal as a deluded, old fool, thus becoming a critic of his own book. (Learn more about this funny and insightful novel in my book Narrative Madness and my many posts about it.)

Parodying chivalric romance by contrasting the lofty story-lines with the hard-edge of reality, Cervantes established two genres: metafiction and realism. Often called the first modern novel, it could also be called the first post-modern novel. It’s a book about books and the effects they have upon our lives, especially when we try to live out our fictions in the real world. Cervantes challenges the notion of objective history and blurs the distinction between fiction and nonfiction. The events are told by a series of authors nested one within the other like Chinese boxes, which draws attention to how stories are told and how each teller alters the tale. In the second volume, Don Quixote and Sancho Panza hear of the publication of the first. They meet a reader and talk to him about their own book. Don Quixote, expecting a heroic romance, is angered by his portrayal as a deluded, old fool, thus becoming a critic of his own book. (Learn more about this funny and insightful novel in my book Narrative Madness and my many posts about it.)

Continue reading “Top Twenty One Metafictional Works: The Story That Swallows Its Tale”