Harold scribbles across the cover, flyleaves and title page with his purple crayon, but then pauses in thought, looking at his squiggles, realizing, perhaps, that they are meaningless. The next page is also a jumble, but the line flattens out, trailing behind Harold, who has begun to walk from left to right. Harold pauses, staring into the blankness of the upper right hand corner. The first text of the story appears under his feet: “One evening, after thinking it over for some time, Harold decided to go for a walk in the moonlight.” The decision to go for a walk, rather than rambling, is what makes the crooked line straight. The first change in Harold’s artistic development is purpose.

Continue reading “A Nightmare Reading of Harold and the Purple Crayon”

Andre Gide adopts the heraldic term mise en abyme, or a shield shown in the center of a shield, to describe a work within a work, like The Mousetrap in Hamlet, but Gide ultimately rejects such examples because The Mousetrap does not represent Hamlet as a whole, but only the actions of the characters within the play (as I discuss in

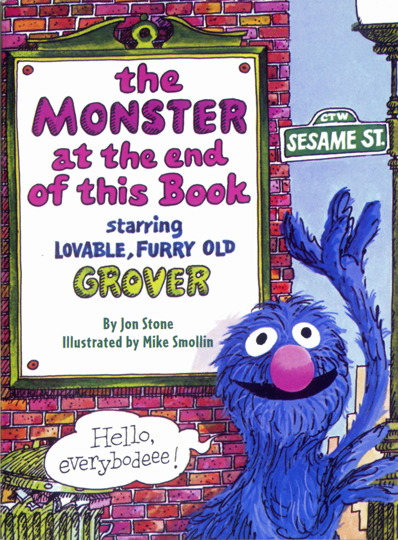

Andre Gide adopts the heraldic term mise en abyme, or a shield shown in the center of a shield, to describe a work within a work, like The Mousetrap in Hamlet, but Gide ultimately rejects such examples because The Mousetrap does not represent Hamlet as a whole, but only the actions of the characters within the play (as I discuss in  A book within a book, a play inside a play, a picture in a picture, these are examples of mise en abyme, a literary term the French writer André Gide borrowed from heraldry. Pronounced “meez en a-beem,” it literally means “placed in the abyss,” or, more simply, “placed in the middle,” and it was used to describe a shield in the middle of a shield, as in this coat of arms of the United Kingdom from 1816-1837. (Image from

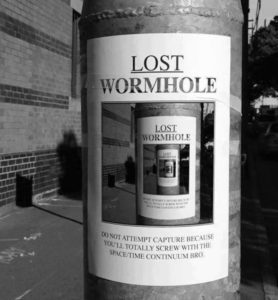

A book within a book, a play inside a play, a picture in a picture, these are examples of mise en abyme, a literary term the French writer André Gide borrowed from heraldry. Pronounced “meez en a-beem,” it literally means “placed in the abyss,” or, more simply, “placed in the middle,” and it was used to describe a shield in the middle of a shield, as in this coat of arms of the United Kingdom from 1816-1837. (Image from  You’ll notice that the shield inside the shield has another shield inside of it. You can imagine yet another inside that one and so on and so on, forever and ever, so I like to think of “mise en abyme” as “into the abyss.” The eye travels down the rabbit hole to infinity, as in this photo of a “Lost Wormhole” from Illuminaughty Boutique’s post “

You’ll notice that the shield inside the shield has another shield inside of it. You can imagine yet another inside that one and so on and so on, forever and ever, so I like to think of “mise en abyme” as “into the abyss.” The eye travels down the rabbit hole to infinity, as in this photo of a “Lost Wormhole” from Illuminaughty Boutique’s post “

This introduction to Donald Barthelme’s short story “The School” is non-fiction. Non-fiction means “not fiction.” Fiction, as you have learned, is a story that is “not true.” In other words non-fiction, on a linguistic level, is “not not-true.” This means, logically, when you cancel out the negatives, that the non-fictional information I am about to give you, is — I am very pleased to say — true.

This introduction to Donald Barthelme’s short story “The School” is non-fiction. Non-fiction means “not fiction.” Fiction, as you have learned, is a story that is “not true.” In other words non-fiction, on a linguistic level, is “not not-true.” This means, logically, when you cancel out the negatives, that the non-fictional information I am about to give you, is — I am very pleased to say — true.