We know the scene: he begins to tell a story by the fire, mumbling, miming, chanting, swaying, and no one pays attention, but he keeps going and there is something about the quiet insistence of his song as it grows louder that makes the woman, grinding ocher, look up. The men, scraping hides, one by one let the flint fall and find stones to sit on. Others notice the group and gather.

They were not like this before; the story has brought them together. In the warmth of the fire, they lean toward the story-teller, who is one of them and yet an outsider: he has gone away for a long time, he is crippled, or strange. Perhaps he is a woman. He tells them the story of the beginning of the world, the birth of the first people, the coming together of a culture, the origin of language and story-telling — a tale they all know, but only he has “the gift, the right, or the duty to tell it” (Nancy 43).

This scene, which takes place again and again, describes the beginning of human consciousness and speech. It is the story of “humanity being born to itself” (Nancy 45). The origin of myth.

Alas, this scene by the fire never took place, at least not in the way we imagine it. The scene itself is a myth. Jean-Luc Nancy calls it the myth of myths. (And we can call it a meta-myth!)

Continue reading “The Myth of Myths: Jean-Luc Nancy’s “Myth Interrupted””

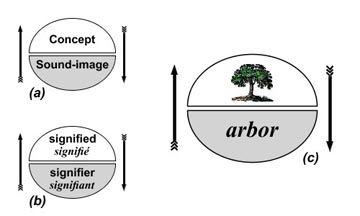

At the beginning of the last century, Ferdinand de Saussure severed language from reality. In his Course in General Linguistics, he explained that a sign is made up of two parts: the signifier and the signified. The signifier is a word, a set of sounds, sometimes represented by letters. The signified is what the signifier arbitrarily refers to. Unfortunately for those who want language to be a transparent window on the world, the signified is not an external object, but a subjective concept.

At the beginning of the last century, Ferdinand de Saussure severed language from reality. In his Course in General Linguistics, he explained that a sign is made up of two parts: the signifier and the signified. The signifier is a word, a set of sounds, sometimes represented by letters. The signified is what the signifier arbitrarily refers to. Unfortunately for those who want language to be a transparent window on the world, the signified is not an external object, but a subjective concept.