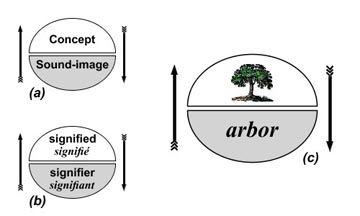

At the beginning of the last century, Ferdinand de Saussure severed language from reality. In his Course in General Linguistics, he explained that a sign is made up of two parts: the signifier and the signified. The signifier is a word, a set of sounds, sometimes represented by letters. The signified is what the signifier arbitrarily refers to. Unfortunately for those who want language to be a transparent window on the world, the signified is not an external object, but a subjective concept.

At the beginning of the last century, Ferdinand de Saussure severed language from reality. In his Course in General Linguistics, he explained that a sign is made up of two parts: the signifier and the signified. The signifier is a word, a set of sounds, sometimes represented by letters. The signified is what the signifier arbitrarily refers to. Unfortunately for those who want language to be a transparent window on the world, the signified is not an external object, but a subjective concept.

A sidewalk (another word for ground) is not a thing, but an idea. After all, we do not experience the rough pavement as a snail or a starling might, who cannot know that the sidewalk is for walking. How could they when they lack the word?

Building on Saussure’s ideas, words not only signify concepts, they signify narrative functions. When the doctor (more of a role than an individual) first squints at a sonogram and says, “It’s a boy,” or “Twin girls,” the declaration influences our names, colors, costumes, toys, words, hand gestures, attitudes and jobs. “Boy” is more than just a linguistic concept, it is a role in a story. We may fight against our gender role, introduce a twist or two, but we are deeply affected by that first designation.

Since infancy, other story words have kept attaching themselves to us: “He’s a thumb-sucker, a Taurus, a middle-child, a joker, a tattletale, a friend, a writer, a Democrat, a player, a teacher, a ghoul.” We may play along with or resist these terms, but they are difficult to escape. When we manage to remove some labels, we merely trade them for others.

We cannot step outside of our narrative language because we are fictions ourselves. Even the precious word “I” — which rises like a monolith above our heads, promising singularity and unity — is an invented word, rather than a natural concept. And that slim word, a simple line, determines how the tale is told: “I act upon the world and the world acts upon me.” Because of the word “I” (and his mate “me”) and a preexisting sentence structure — subject – verb – object — I am forever separated from the world around me. This is why we speak of internal and external worlds, self and other, me and you, us and them. Even those who believe in the transparency of language describe it as separating them from the world like a window.

Words are not merely concepts, they imply narrative functions, the roles these words will play. Language and grammar exist before us and we must fit ourselves within linguistic structures that determine how we tell our stories and even how we live them.

(The second part of a six part series, following “Trapped in Narrative Language” and to be followed by “Understanding and Narrative Structures.” For more about how language affects reality, check out “The Limits of Language: Seuss Beyond Zebra,” “Penetrate the Power of Words” and “How Language Speaks You.” To read more about the constructed “I,” read “Who is Writing This?” “Where Did I Come from?” and “I am the One the Writer of this Sentence is Referring to.” Read more about all these theories in my book Narrative Madness, available at narrativemadness.com and on Amazon.)

Work Cited

de Saussure, Ferdinand. “Nature of the Linguistic Sign.” From Course in General Linguistics. The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2001. 963-966.