We don’t just speak with our mouths. We also speak with our bodies, our hands, our faces, our eyes, our respiratory systems, our lips, our tongues, our mouths, our brains. Various sayings emphasize the importance of these body parts in the production of language. Making faces. Her eyes spoke volumes. Hot air. Words dripped from her lips like honey. Mother tongue (implying that the language gives birth to the person). Mouthing off. Getting something off your mind. We used to talk about venting the spleen, letting out our angry feelings, but the truth is we don’t use the spleen. Speaking involves only certain parts of the body, so “I” tends to represent those parts.

We don’t just speak with our mouths. We also speak with our bodies, our hands, our faces, our eyes, our respiratory systems, our lips, our tongues, our mouths, our brains. Various sayings emphasize the importance of these body parts in the production of language. Making faces. Her eyes spoke volumes. Hot air. Words dripped from her lips like honey. Mother tongue (implying that the language gives birth to the person). Mouthing off. Getting something off your mind. We used to talk about venting the spleen, letting out our angry feelings, but the truth is we don’t use the spleen. Speaking involves only certain parts of the body, so “I” tends to represent those parts.

Continue reading “What Parts of Your Body Do You Speak With?”

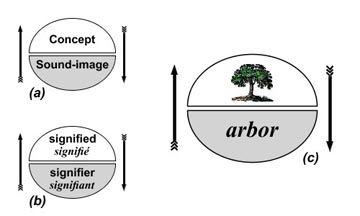

At the beginning of the last century, Ferdinand de Saussure severed language from reality. In his Course in General Linguistics, he explained that a sign is made up of two parts: the signifier and the signified. The signifier is a word, a set of sounds, sometimes represented by letters. The signified is what the signifier arbitrarily refers to. Unfortunately for those who want language to be a transparent window on the world, the signified is not an external object, but a subjective concept.

At the beginning of the last century, Ferdinand de Saussure severed language from reality. In his Course in General Linguistics, he explained that a sign is made up of two parts: the signifier and the signified. The signifier is a word, a set of sounds, sometimes represented by letters. The signified is what the signifier arbitrarily refers to. Unfortunately for those who want language to be a transparent window on the world, the signified is not an external object, but a subjective concept.