When Donald Barthelme took popular characters (Batman and the Joker) and placed them in unusual, postmodern situations in his short story “The Joker’s Greatest Triumph” (1967), he was doing something new: taking an old, familiar story and turning it inside out. He did something as daring when he reinvented the story of Snow White in his 1967 novel of the same name.

When Donald Barthelme took popular characters (Batman and the Joker) and placed them in unusual, postmodern situations in his short story “The Joker’s Greatest Triumph” (1967), he was doing something new: taking an old, familiar story and turning it inside out. He did something as daring when he reinvented the story of Snow White in his 1967 novel of the same name.

The importance of these literary experiments can be seen in the influence they have had on generations of writers. Now reinventions of popular stories (such as the inversion of the superhero comic in Alan Moore’s Watchmen) and retellings of fairy tales (like Gregory Maguire’s Wicked) are as common as a cold, but when my paperback edition of Snow White was reprinted in 1971, the experiment was unusual enough to warrant this statement on the back: “Donald Barthelme’s Snow White is not the fairy tale you remember. But it’s the one you will never forget.”

Continue reading “Do You Like the Story So Far?: Metafiction in Barthelme’s Snow White”

Andre Gide adopts the heraldic term mise en abyme, or a shield shown in the center of a shield, to describe a work within a work, like The Mousetrap in Hamlet, but Gide ultimately rejects such examples because The Mousetrap does not represent Hamlet as a whole, but only the actions of the characters within the play (as I discuss in

Andre Gide adopts the heraldic term mise en abyme, or a shield shown in the center of a shield, to describe a work within a work, like The Mousetrap in Hamlet, but Gide ultimately rejects such examples because The Mousetrap does not represent Hamlet as a whole, but only the actions of the characters within the play (as I discuss in  A book within a book, a play inside a play, a picture in a picture, these are examples of mise en abyme, a literary term the French writer André Gide borrowed from heraldry. Pronounced “meez en a-beem,” it literally means “placed in the abyss,” or, more simply, “placed in the middle,” and it was used to describe a shield in the middle of a shield, as in this coat of arms of the United Kingdom from 1816-1837. (Image from

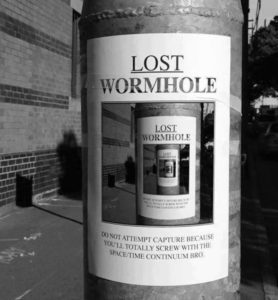

A book within a book, a play inside a play, a picture in a picture, these are examples of mise en abyme, a literary term the French writer André Gide borrowed from heraldry. Pronounced “meez en a-beem,” it literally means “placed in the abyss,” or, more simply, “placed in the middle,” and it was used to describe a shield in the middle of a shield, as in this coat of arms of the United Kingdom from 1816-1837. (Image from  You’ll notice that the shield inside the shield has another shield inside of it. You can imagine yet another inside that one and so on and so on, forever and ever, so I like to think of “mise en abyme” as “into the abyss.” The eye travels down the rabbit hole to infinity, as in this photo of a “Lost Wormhole” from Illuminaughty Boutique’s post “

You’ll notice that the shield inside the shield has another shield inside of it. You can imagine yet another inside that one and so on and so on, forever and ever, so I like to think of “mise en abyme” as “into the abyss.” The eye travels down the rabbit hole to infinity, as in this photo of a “Lost Wormhole” from Illuminaughty Boutique’s post “ Makers of false coins are not the counterfeiters that most concern André Gide in his novel The Counterfeiters (Les Faux-Monnayeurs). The counterfeiters that matter most are the writers: the character Édouard, the narrator who speaks for Gide, and even Gide himself. The fictional Édouard writes at length in his journal about a book he is planning to write, a book called The Counterfeiters, which shares not only the same title as Gide’s novel, but also its subject and themes. Nevertheless, The Counterfeiters is not a book within a book as many critics claim because the reader is never allowed to read Édouard’s novel, only his notes.

Makers of false coins are not the counterfeiters that most concern André Gide in his novel The Counterfeiters (Les Faux-Monnayeurs). The counterfeiters that matter most are the writers: the character Édouard, the narrator who speaks for Gide, and even Gide himself. The fictional Édouard writes at length in his journal about a book he is planning to write, a book called The Counterfeiters, which shares not only the same title as Gide’s novel, but also its subject and themes. Nevertheless, The Counterfeiters is not a book within a book as many critics claim because the reader is never allowed to read Édouard’s novel, only his notes.