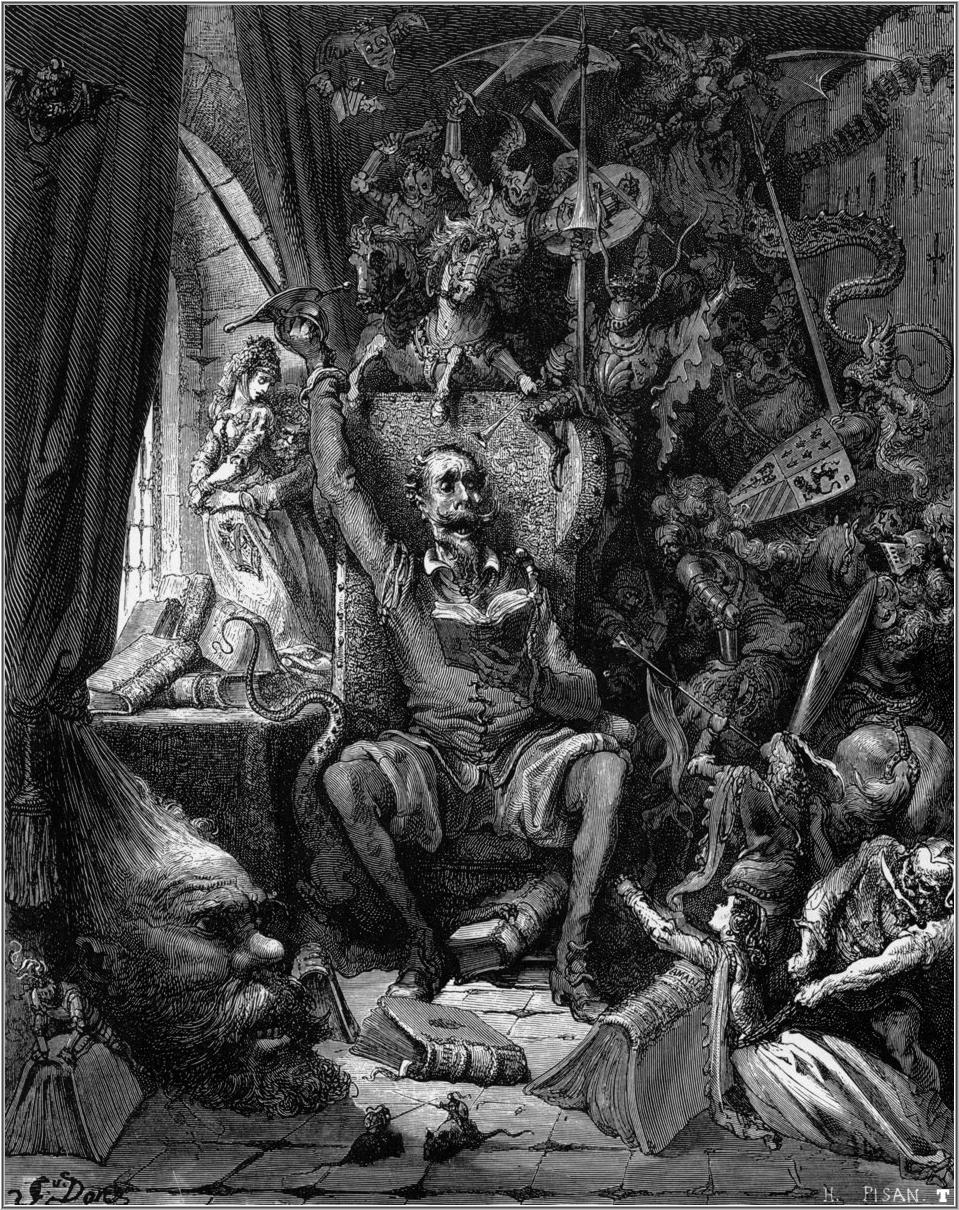

Our stories have driven us mad.

All of us. You, me and Don Quixote all suffer from narrative madness. Alas, I can not cure you, but I can treat the symptoms with a gloppy plaster of metafiction.

Like the ingenious man of La Mancha, we wander lost through clouds of story, never directly experiencing our surroundings, others, or events. On the day he sallied forth, the self-christened Don Quixote encountered an inn:

“And as whatever our adventurer thought, saw, or imagined, seemed to him to be done and transacted in the manner he had read of, immediately, at sight of the inn, he fancied it to be a castle, with four turrets and battlements of refulgent silver, together with its drawbridge, deep moat, and all the appurtenances with which such castles are usually described” (Cervantes 28).

Gustave Doré

We may think the knight deranged for seeing a castle where there was none, but what did you picture? I imagined an old, white-washed inn with a courtyard full of chickens, warped, wooden tables in a dingy dining room, and dusty rooms. Many stories leapt to mind: drinking and dining, bantering and brawling, whoring and travelling. Was my inn any realer than Don Quixote’s castle?

(Grammatically, “realer” does not exist in the English language. Since “real” is an absolute adjective — like “infinity” — we cannot compare its reality to anything else. Our language forces us to decide whether something is real or not. This grammatical rule will not stop me, however, since I will be arguing that “real” should be a relative term, as in the statement, “Infinity is not as real as the limited, but expanding universe.”)

You may object that reading about an inn is different than seeing a castle; a reader must imagine what is not physically present. Yet what do you see when you actually stand in front of a youth hostel or a five-star hotel? Before you walk through the door, don’t you picture “all the appurtenances” with which hostels and hotels “are usually described”? You assume these buildings have certain amenities that you cannot see, whether a shared kitchen or an exclusive health spa.

And you associate these structures with certain characters and events. For me, “a hostel” means friendly strangers and youthful adventure, “a five-star hotel” invokes visiting dignitaries and coked-up rock stars. In the first, I am a character, in the second I am not, since I have only walked through the lobbies of five-star hotels. When you stay at a “motel,” who goes with you and what happens behind the heavy, green curtains? We can only understand these buildings as settings for stories, stories in which we are normally the central character, the hero (or anti-hero).

We access reality primarily through narrative language. We can not even fathom the earth beneath our feet, except as part of the tale we are telling. Rather than a solid foundation, we stand upon a fictional concept. The words that we use indicate what part the ground is going to play in our chronicle: soil, parking lot, path, tarmac, tundra. We plant and harvest crops in soil, we hike up and down a path, we park and make-out in the parking lot, we take off and crash on the tarmac, and we bounce across or study the tundra. Language precedes perception and determines our actions.

(First part of a six part series, followed by “Extending the Linguistic ‘Concept’ to Include ‘Narrative Function.” To learn more about Don Quixote and these theories, read my book Narrative Madness, available on Amazon.)

Engraving by Gustave Dore.

Cervantes, Miguel de. Don Quixote de la Mancha. Trans. Charles Jarvis. Ed. E. C. Riley. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992. Print.