While Miguel de Cervantes was writing a tale about a mad knight, scientists were discovering and describing a rational order to the cosmos. Between the publication of the first book of Don Quijote in 1605 and and the second in 1615, Johannes Kepler proposed the first two laws of planetary motion, and Galileo Galilei made telescopic observations that proved the heliocentric model of the solar system proposed by Copernicus sixty years earlier. To these scientists, the universe appeared to be an organized system, operating according to observable, objective laws.

In his article “Chaotic Quijote: Complexity, Nonlinearity and Perspectivism,” Cory A. Reed argues that Cervantes’ metafictional novel anticipates chaos theory: “Like chaos theory itself, Cervantes’ novel challenges the reliability of determinism, objectivity, and literalism that would soon be adopted by the Newtonian and Cartesian models of scientific investigation” (Reed 738). In contrast to the scientists of his day (and all others up until Albert Einstein and Werner Heisenberg), Cervantes represented reality as contradictory, random and subjective.

Continue reading “Metafiction and Chaos Theory: Cory A. Reed’s “Chaotic Quijote””

Andre Gide adopts the heraldic term mise en abyme, or a shield shown in the center of a shield, to describe a work within a work, like The Mousetrap in Hamlet, but Gide ultimately rejects such examples because The Mousetrap does not represent Hamlet as a whole, but only the actions of the characters within the play (as I discuss in

Andre Gide adopts the heraldic term mise en abyme, or a shield shown in the center of a shield, to describe a work within a work, like The Mousetrap in Hamlet, but Gide ultimately rejects such examples because The Mousetrap does not represent Hamlet as a whole, but only the actions of the characters within the play (as I discuss in  A book within a book, a play inside a play, a picture in a picture, these are examples of mise en abyme, a literary term the French writer André Gide borrowed from heraldry. Pronounced “meez en a-beem,” it literally means “placed in the abyss,” or, more simply, “placed in the middle,” and it was used to describe a shield in the middle of a shield, as in this coat of arms of the United Kingdom from 1816-1837. (Image from

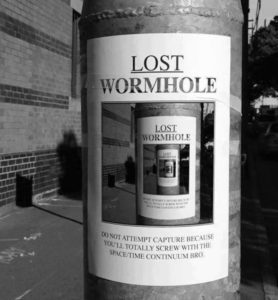

A book within a book, a play inside a play, a picture in a picture, these are examples of mise en abyme, a literary term the French writer André Gide borrowed from heraldry. Pronounced “meez en a-beem,” it literally means “placed in the abyss,” or, more simply, “placed in the middle,” and it was used to describe a shield in the middle of a shield, as in this coat of arms of the United Kingdom from 1816-1837. (Image from  You’ll notice that the shield inside the shield has another shield inside of it. You can imagine yet another inside that one and so on and so on, forever and ever, so I like to think of “mise en abyme” as “into the abyss.” The eye travels down the rabbit hole to infinity, as in this photo of a “Lost Wormhole” from Illuminaughty Boutique’s post “

You’ll notice that the shield inside the shield has another shield inside of it. You can imagine yet another inside that one and so on and so on, forever and ever, so I like to think of “mise en abyme” as “into the abyss.” The eye travels down the rabbit hole to infinity, as in this photo of a “Lost Wormhole” from Illuminaughty Boutique’s post “ Makers of false coins are not the counterfeiters that most concern André Gide in his novel The Counterfeiters (Les Faux-Monnayeurs). The counterfeiters that matter most are the writers: the character Édouard, the narrator who speaks for Gide, and even Gide himself. The fictional Édouard writes at length in his journal about a book he is planning to write, a book called The Counterfeiters, which shares not only the same title as Gide’s novel, but also its subject and themes. Nevertheless, The Counterfeiters is not a book within a book as many critics claim because the reader is never allowed to read Édouard’s novel, only his notes.

Makers of false coins are not the counterfeiters that most concern André Gide in his novel The Counterfeiters (Les Faux-Monnayeurs). The counterfeiters that matter most are the writers: the character Édouard, the narrator who speaks for Gide, and even Gide himself. The fictional Édouard writes at length in his journal about a book he is planning to write, a book called The Counterfeiters, which shares not only the same title as Gide’s novel, but also its subject and themes. Nevertheless, The Counterfeiters is not a book within a book as many critics claim because the reader is never allowed to read Édouard’s novel, only his notes.