Language and storytelling arose as a means of creating and maintaining social ties. Tribes then spread across the planet, trading materials, goods, technology, information and stories, so it should not come as a surprise that our narratives are similar worldwide. As humans, we make up stories habitually in order to understand the universe, ourselves and others, but we can only do so within established narrative language (as we have seen) and (this is the new part) preexisting forms and genres.

Language and storytelling arose as a means of creating and maintaining social ties. Tribes then spread across the planet, trading materials, goods, technology, information and stories, so it should not come as a surprise that our narratives are similar worldwide. As humans, we make up stories habitually in order to understand the universe, ourselves and others, but we can only do so within established narrative language (as we have seen) and (this is the new part) preexisting forms and genres.

Continue reading “The Plagiarized Hero: The Hero with a Thousand Borrowed Faces”

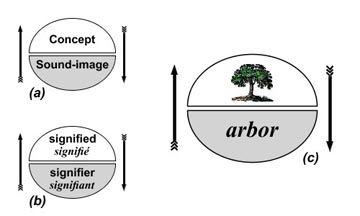

At the beginning of the last century, Ferdinand de Saussure severed language from reality. In his Course in General Linguistics, he explained that a sign is made up of two parts: the signifier and the signified. The signifier is a word, a set of sounds, sometimes represented by letters. The signified is what the signifier arbitrarily refers to. Unfortunately for those who want language to be a transparent window on the world, the signified is not an external object, but a subjective concept.

At the beginning of the last century, Ferdinand de Saussure severed language from reality. In his Course in General Linguistics, he explained that a sign is made up of two parts: the signifier and the signified. The signifier is a word, a set of sounds, sometimes represented by letters. The signified is what the signifier arbitrarily refers to. Unfortunately for those who want language to be a transparent window on the world, the signified is not an external object, but a subjective concept.