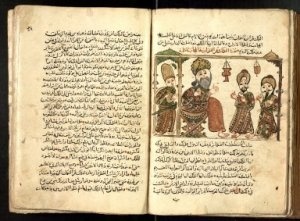

The Arabian Nights is a story of stories. Not only is it a rich interwoven carpet of stories within stories within stories within stories, it is also a story about the power of stories, the power of fiction to save lives, to tame murderers and to change the world.

The most authentic English translation (by Husain Haddawy) begins, “It is related — but God knows and sees best what lies hidden in the old accounts of bygone people and times — that long ago, during the time of the Sasanid dynasty, in the peninsulas of India and Indochina, there lived two kings who were brothers” (5), reminding us from the very start that we are reading a story “related” by someone. Unlike the other stories in The Arabian Nights, we do not know who is telling us the frame story, the big tale that includes all other tales, instead we get the passive form “it is related,” followed by a warning that only God knows “what lies hidden in the old accounts,” in other words only Allah knows the truth of these fictions or even the secret meaning of them.

The most authentic English translation (by Husain Haddawy) begins, “It is related — but God knows and sees best what lies hidden in the old accounts of bygone people and times — that long ago, during the time of the Sasanid dynasty, in the peninsulas of India and Indochina, there lived two kings who were brothers” (5), reminding us from the very start that we are reading a story “related” by someone. Unlike the other stories in The Arabian Nights, we do not know who is telling us the frame story, the big tale that includes all other tales, instead we get the passive form “it is related,” followed by a warning that only God knows “what lies hidden in the old accounts,” in other words only Allah knows the truth of these fictions or even the secret meaning of them.

Continue reading “1001 Ways to Save Your Life: Shahrazad and The Arabian Nights”

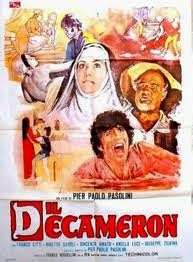

In Pasolini’s filmed version of The Decameron, he inexplicably leaves off Boccaccio’s frame story of a group of seven women and three men who retire to an estate in the country to avoid the plague that is ravaging Florence. There they tell each other stories to entertain, to cheer, and to instruct each other. Pasolini instead jumps right into a story, plays it out, then moves to another without explanation. He tells some interesting stories (and some of them are very sexy), but the film left me wondering why? What’s the point?

In Pasolini’s filmed version of The Decameron, he inexplicably leaves off Boccaccio’s frame story of a group of seven women and three men who retire to an estate in the country to avoid the plague that is ravaging Florence. There they tell each other stories to entertain, to cheer, and to instruct each other. Pasolini instead jumps right into a story, plays it out, then moves to another without explanation. He tells some interesting stories (and some of them are very sexy), but the film left me wondering why? What’s the point?