“Words are not magical,” one professor said, waving her hand to indicate the empty space in the center of the ring of chairs. “When I say ‘table,’ no table appears.”

In her attempts to steer us away from the metaphysical and romantic views of language and ground literary theory and discussion in the relatively more scientific and pragmatic language of structuralism, she inadvertently convinced me that words were magical. For a table did appear.

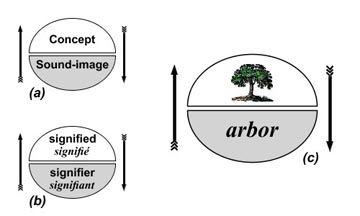

At the beginning of the last century, Ferdinand de Saussure severed language from reality. In his Course in General Linguistics, he explained that a sign is made up of two parts: the signifier and the signified. The signifier is a word, a set of sounds, sometimes represented by letters. The signified is what the signifier arbitrarily refers to. Unfortunately for those who want language to be a transparent window on the world, the signified is not an external object, but a subjective concept.

At the beginning of the last century, Ferdinand de Saussure severed language from reality. In his Course in General Linguistics, he explained that a sign is made up of two parts: the signifier and the signified. The signifier is a word, a set of sounds, sometimes represented by letters. The signified is what the signifier arbitrarily refers to. Unfortunately for those who want language to be a transparent window on the world, the signified is not an external object, but a subjective concept.