Cervantes’ preface to Don Quixote is a caustic satire of academic writing, just as valid today as it was four hundred and five years ago. Full of delicious irony, Cervantes brags with the deepest humility. He points out the flaws in the book are its qualities.

Chaucer: A Bad Poet and a Didactic Bore

What? What did that title just say? Now hold on just a moment! Who the hell does this Ronosaurus Rex think he is anyway, calling the first Great Poet (with a capital G and a capital P) in the English language “a bad poet and a didactic bore”? When I read “The Wife of Bath’s Tale,” for example, I remember delightful comedy, complex poetry and deep insight.

The Decameron With and Without a Frame

In Pasolini’s filmed version of The Decameron, he inexplicably leaves off Boccaccio’s frame story of a group of seven women and three men who retire to an estate in the country to avoid the plague that is ravaging Florence. There they tell each other stories to entertain, to cheer, and to instruct each other. Pasolini instead jumps right into a story, plays it out, then moves to another without explanation. He tells some interesting stories (and some of them are very sexy), but the film left me wondering why? What’s the point?

In Pasolini’s filmed version of The Decameron, he inexplicably leaves off Boccaccio’s frame story of a group of seven women and three men who retire to an estate in the country to avoid the plague that is ravaging Florence. There they tell each other stories to entertain, to cheer, and to instruct each other. Pasolini instead jumps right into a story, plays it out, then moves to another without explanation. He tells some interesting stories (and some of them are very sexy), but the film left me wondering why? What’s the point?

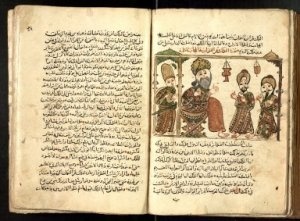

10,001 Nights: The Frame Stories Outside the Frame Story

Shahrazad’s story may frame the stories within The Arabian Nights, but many, many, many more stories surround it.

First of all, there is the complicated story of the Nights framing itself. The tales can be traced back to various ethnic origins, especially Indian, Persian and Arabic. In the endless tellings and retellings these stories were gradually reshaped to fit the Arabic culture of the middle ages, which gives the stories a “homogeneity or distinctive synthesis that marks the cultural and artistic history of Islam” (xiv).

Continue reading “10,001 Nights: The Frame Stories Outside the Frame Story”

The Power of Stories to Change the World: Another Arabian Night

At the end of 1001 Ways to Save Your Life, Shahrayar was trying to save her life by telling a story to the murderous, mysogonistic Kaliph. She says her story “will cause the king to stop his practice, save myself and deliver the people” (21). The first story she told was of a merchant who inadvertently killed the son of a genie, by tossing away the pits of dates he was eating. The demon was about to slay the merchant, he raised his sword in the air–

At the end of 1001 Ways to Save Your Life, Shahrayar was trying to save her life by telling a story to the murderous, mysogonistic Kaliph. She says her story “will cause the king to stop his practice, save myself and deliver the people” (21). The first story she told was of a merchant who inadvertently killed the son of a genie, by tossing away the pits of dates he was eating. The demon was about to slay the merchant, he raised his sword in the air–

Continue reading “The Power of Stories to Change the World: Another Arabian Night”

1001 Ways to Save Your Life: Shahrazad and The Arabian Nights

The Arabian Nights is a story of stories. Not only is it a rich interwoven carpet of stories within stories within stories within stories, it is also a story about the power of stories, the power of fiction to save lives, to tame murderers and to change the world.

The most authentic English translation (by Husain Haddawy) begins, “It is related — but God knows and sees best what lies hidden in the old accounts of bygone people and times — that long ago, during the time of the Sasanid dynasty, in the peninsulas of India and Indochina, there lived two kings who were brothers” (5), reminding us from the very start that we are reading a story “related” by someone. Unlike the other stories in The Arabian Nights, we do not know who is telling us the frame story, the big tale that includes all other tales, instead we get the passive form “it is related,” followed by a warning that only God knows “what lies hidden in the old accounts,” in other words only Allah knows the truth of these fictions or even the secret meaning of them.

The most authentic English translation (by Husain Haddawy) begins, “It is related — but God knows and sees best what lies hidden in the old accounts of bygone people and times — that long ago, during the time of the Sasanid dynasty, in the peninsulas of India and Indochina, there lived two kings who were brothers” (5), reminding us from the very start that we are reading a story “related” by someone. Unlike the other stories in The Arabian Nights, we do not know who is telling us the frame story, the big tale that includes all other tales, instead we get the passive form “it is related,” followed by a warning that only God knows “what lies hidden in the old accounts,” in other words only Allah knows the truth of these fictions or even the secret meaning of them.

Continue reading “1001 Ways to Save Your Life: Shahrazad and The Arabian Nights”

The Early History of Metafiction

What are the earliest instances of metafiction, or fiction about fiction? I don’t know much about early Chinese literature, but the story I told of the invention of writing in Hunters, the First Readers to Write a Story could be called metafictional, since it is a story about the invention of writing itself.

Grab Your Ledgers: Writing is Accounting

(This post is best read with a beer and a piece of toast.)

Accountants were the first writers. Well, maybe it’s more accurate to say that merchants in ancient Sumeria developed the cuneiform script around 2500 B.C. for accounting purposes. We want to be factual. Let me remind you that this is non-fiction. (Nevermind that the date is appoximate.) But to tell you the history of writing, I need to talk about grass and how we learned to eat it, the technology that has most drastically transformed the face of the planet.

Hunters Reading Signs: The Origin of Writing?

The technique of examining and interpreting signs, which may be called “reading,” can be traced back to hunting. Was hunting, then, the origin of writing?

Many animals track by smell, which communicates directly to the instincts. Does it smell bad? Stay away! Does it smell good? Follow it and eat it! When a wolf comes across the scent, it doesn’t wonder which direction to go, it doesn’t interpret the smell. If the wolf turns left and the yummy deer smell fades, it turns to the right where the smell is fresher.

Continue reading “Hunters Reading Signs: The Origin of Writing?”

A Rain of Ink: Metafiction in Charles Dicken’s Bleak House

Bleak House by Charles Dickens is a printed text and the book frequently reminds readers of that fact, so that readers can not accept the text literally, but are goaded into carefully and skeptically examining the two narratives and the various documents central to the story.

Continue reading “A Rain of Ink: Metafiction in Charles Dicken’s Bleak House”