Since we humans construct our narratives and memories socially, we could ask, “Do we have a collective memory?” Frederic Bartlett, often called the first experimental psychologist, criticized the concept, since “collective memory” seems to suggest a group brain. Societies don’t have brains. We must understand group memory, then, as distributed in the minds of individuals, in discourse, and in symbolic records. “Collective memory” is just a metaphor and taking it too literally is sign of narrative madness.

Since we humans construct our narratives and memories socially, we could ask, “Do we have a collective memory?” Frederic Bartlett, often called the first experimental psychologist, criticized the concept, since “collective memory” seems to suggest a group brain. Societies don’t have brains. We must understand group memory, then, as distributed in the minds of individuals, in discourse, and in symbolic records. “Collective memory” is just a metaphor and taking it too literally is sign of narrative madness.

Tag: narrative

Relevance of Metafiction in the Age of Information

We are flooded with narrative, drowning in astronomical numbers of stories from paperbacks, movies, newspapers, television, magazines, fan fictions, computer games, and, most of all, the Internet. How can we cope with these stories? What do we do with them?

We are flooded with narrative, drowning in astronomical numbers of stories from paperbacks, movies, newspapers, television, magazines, fan fictions, computer games, and, most of all, the Internet. How can we cope with these stories? What do we do with them?

Meta-awareness is more important more than ever, if we are to understand our storied universe. Yet how can we know what is real with reality TV on every channel? Most of us are smart enough to know that the presence of a camera always causes people to act differently than they would otherwise. Although reality TV is realer than a sit com, we recognize that it is not as real as a news broadcast.

Continue reading “Relevance of Metafiction in the Age of Information”

To Understand, We Must Produce Narrative

Like language, narrative refers to concept rather than reality. The structuralist description of the sign can be extended to narrative, since both words and stories are symbols played out across time. A word occurs as a sequence, as when we say or read “T – U – N – D – R – A.” Similarly, a narrative may be defined as signs in a series. The story then can be considered a sign itself, an arbitrary signifier, referring not to events in the real world, but to a subjective concept of what happened, is happening and will happen.

(Diagrams of the plot from Laurence Stern’s Tristram Shandy)

Trapped in Narrative Language

Our stories have driven us mad.

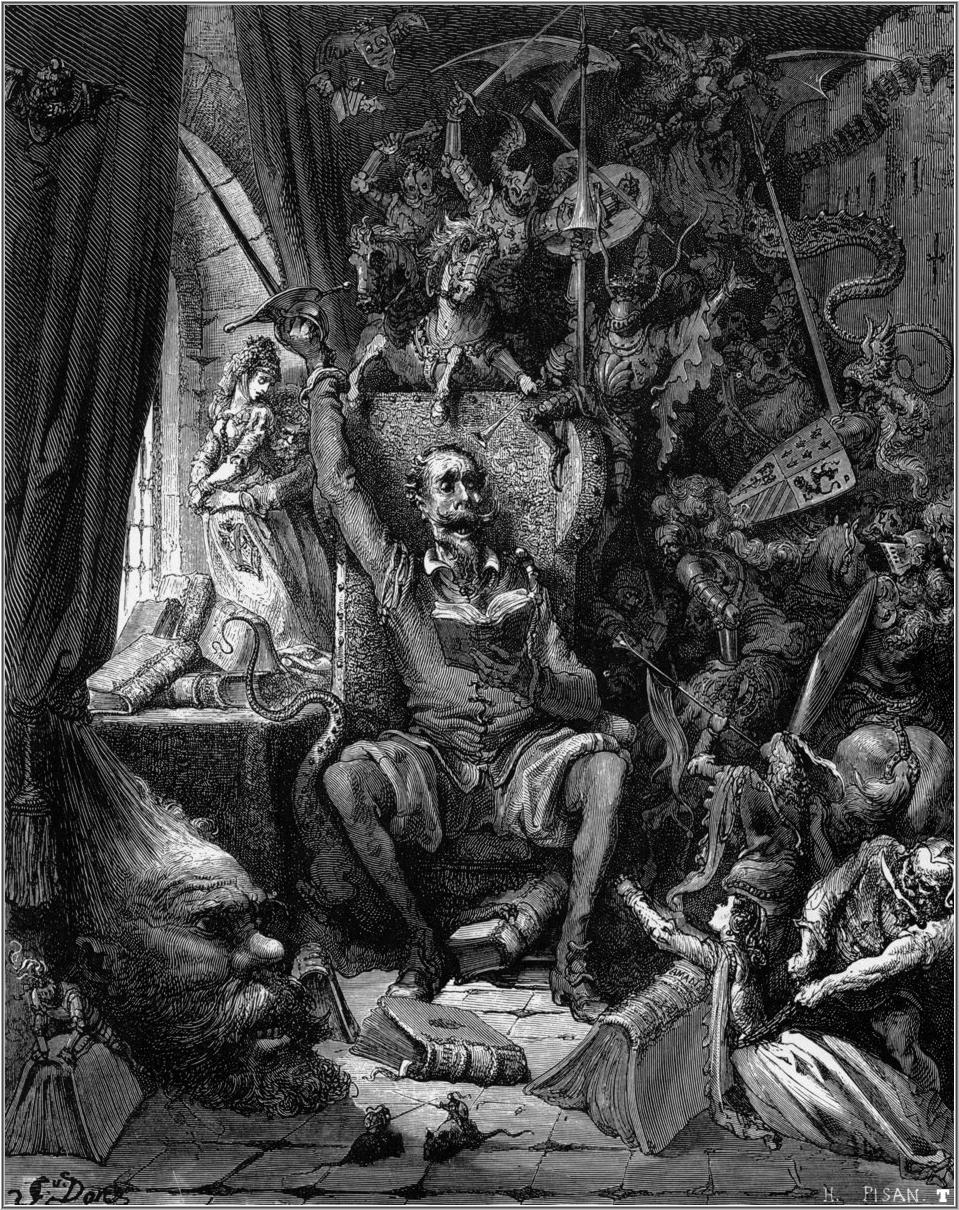

All of us. You, me and Don Quixote all suffer from narrative madness. Alas, I can not cure you, but I can treat the symptoms with a gloppy plaster of metafiction.

Like the ingenious man of La Mancha, we wander lost through clouds of story, never directly experiencing our surroundings, others, or events. On the day he sallied forth, the self-christened Don Quixote encountered an inn:

“And as whatever our adventurer thought, saw, or imagined, seemed to him to be done and transacted in the manner he had read of, immediately, at sight of the inn, he fancied it to be a castle, with four turrets and battlements of refulgent silver, together with its drawbridge, deep moat, and all the appurtenances with which such castles are usually described” (Cervantes 28).

Gustave Doré