Fiction about fiction is metafiction, which allow writers and readers to examine the trickiness of storytelling. Here are the best works of metafiction in chronological order. For a much longer list, see my post 111 Best Works of Metafiction.

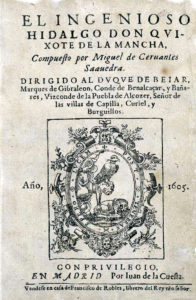

1. Cervantes, Miguel. Don Quixote. 1605.

Parodying chivalric romance by contrasting the lofty story-lines with the hard-edge of reality, Cervantes established two genres: metafiction and realism. Often called the first modern novel, it could also be called the first post-modern novel. It’s a book about books and the effects they have upon our lives, especially when we try to live out our fictions in the real world. Cervantes challenges the notion of objective history and blurs the distinction between fiction and nonfiction. The events are told by a series of authors nested one within the other like Chinese boxes, which draws attention to how stories are told and how each teller alters the tale. In the second volume, Don Quixote and Sancho Panza hear of the publication of the first. They meet a reader and talk to him about their own book. Don Quixote, expecting a heroic romance, is angered by his portrayal as a deluded, old fool, thus becoming a critic of his own book. (Learn more about this funny and insightful novel in my book Narrative Madness and my many posts about it.)

Parodying chivalric romance by contrasting the lofty story-lines with the hard-edge of reality, Cervantes established two genres: metafiction and realism. Often called the first modern novel, it could also be called the first post-modern novel. It’s a book about books and the effects they have upon our lives, especially when we try to live out our fictions in the real world. Cervantes challenges the notion of objective history and blurs the distinction between fiction and nonfiction. The events are told by a series of authors nested one within the other like Chinese boxes, which draws attention to how stories are told and how each teller alters the tale. In the second volume, Don Quixote and Sancho Panza hear of the publication of the first. They meet a reader and talk to him about their own book. Don Quixote, expecting a heroic romance, is angered by his portrayal as a deluded, old fool, thus becoming a critic of his own book. (Learn more about this funny and insightful novel in my book Narrative Madness and my many posts about it.)

Continue reading “Top Twenty One Metafictional Works: The Story That Swallows Its Tale”

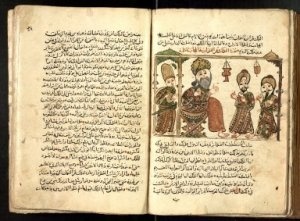

The Syrian manuscripts attempted to preserve and reproduce the “original” which stopped at two hundred and seventy-one nights but the Egyptian branch of manuscripts, Haddawy tells us in the introduction, “shows a proliferation that produced an abundance of poisonous fruits that proved almost fatal to the original” (Nights xv). Haddawy calls such additions “poisonous fruit” because he feels they destroyed its Arabic homogeneity. Besides deleting, modifying, adding, and borrowing from each other, “the copyist, driven to complete one thousand and one nights, kept adding folk tales, fables and anecdotes from Indian, Persian and Turkish, as well as indigenous sources, both from the oral and from the written traditions” (Nights xv). The tale of Sinbad is one such addition (the adventure is old, but its inclusion in The Arabian Nights is not). “The Story of Aladdin and the Magic Lamp” is actually a forgery written by a Frenchman named Galland and then translated into Arabic by a Syrian living in Paris to make it seem authentic, as evidenced by the French syntax and certain turns of phrase (Nights xvi).

The Syrian manuscripts attempted to preserve and reproduce the “original” which stopped at two hundred and seventy-one nights but the Egyptian branch of manuscripts, Haddawy tells us in the introduction, “shows a proliferation that produced an abundance of poisonous fruits that proved almost fatal to the original” (Nights xv). Haddawy calls such additions “poisonous fruit” because he feels they destroyed its Arabic homogeneity. Besides deleting, modifying, adding, and borrowing from each other, “the copyist, driven to complete one thousand and one nights, kept adding folk tales, fables and anecdotes from Indian, Persian and Turkish, as well as indigenous sources, both from the oral and from the written traditions” (Nights xv). The tale of Sinbad is one such addition (the adventure is old, but its inclusion in The Arabian Nights is not). “The Story of Aladdin and the Magic Lamp” is actually a forgery written by a Frenchman named Galland and then translated into Arabic by a Syrian living in Paris to make it seem authentic, as evidenced by the French syntax and certain turns of phrase (Nights xvi).

Freud expanded the concept of the pleasure principle, as he developed his theory of the death drive, into a broader, more inclusive life drive, which he associated with Eros, the Greek god of sexual love: “the libido of our sexual instincts would coincide with the Eros of the poets and philosophers which holds all living things together” (Freud, “Beyond” 619). Eros represents not only the sexual instincts, but thirst, hunger, self-preservation, reproduction, and creativity. Shahrazad, who holds all the living tales of the book together, is “intelligent, knowledgeable, wise and refined. She had read and learned” (Nights 15). This educated woman approaches her father, the vizier, and demands that he offer her to the killer king.

Freud expanded the concept of the pleasure principle, as he developed his theory of the death drive, into a broader, more inclusive life drive, which he associated with Eros, the Greek god of sexual love: “the libido of our sexual instincts would coincide with the Eros of the poets and philosophers which holds all living things together” (Freud, “Beyond” 619). Eros represents not only the sexual instincts, but thirst, hunger, self-preservation, reproduction, and creativity. Shahrazad, who holds all the living tales of the book together, is “intelligent, knowledgeable, wise and refined. She had read and learned” (Nights 15). This educated woman approaches her father, the vizier, and demands that he offer her to the killer king.

The sexual instinct, which Freud said is so hard to “educate,” can be carried to such extremes that pleasure becomes destructive, even self-destructive. From the point of view of self-preservation, Freud writes, the pleasure principle is “from the very outset inefficient and even highly dangerous” (Freud, “Beyond” 597). The prologue, which establishes the frame story of King Shahrayar and Shahrazad, is dripping with destructive sexuality.

The sexual instinct, which Freud said is so hard to “educate,” can be carried to such extremes that pleasure becomes destructive, even self-destructive. From the point of view of self-preservation, Freud writes, the pleasure principle is “from the very outset inefficient and even highly dangerous” (Freud, “Beyond” 597). The prologue, which establishes the frame story of King Shahrayar and Shahrazad, is dripping with destructive sexuality.