Who is I? According to the Oxford English Dictionary, “I” is “used by the speaker or writer to refer to himself or herself.” Simple enough, but let’s think this out. The dictionary says that “I” is “used by the speaker or writer,” implying that “I” and “the speaker or writer” are not the same. How can this be? Well, one is a word and the other is a person. That “I” appears in the dictionary proves that “I” is a written or spoken symbol. Okay, so? The problem is that we confuse ourselves with that symbol. I think I am the “I.”

Continue reading “I am the One the Writer of This Sentence is Referring to”

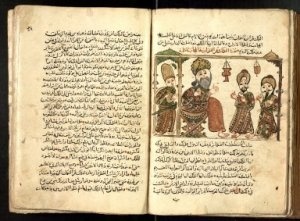

The Syrian manuscripts attempted to preserve and reproduce the “original” which stopped at two hundred and seventy-one nights but the Egyptian branch of manuscripts, Haddawy tells us in the introduction, “shows a proliferation that produced an abundance of poisonous fruits that proved almost fatal to the original” (Nights xv). Haddawy calls such additions “poisonous fruit” because he feels they destroyed its Arabic homogeneity. Besides deleting, modifying, adding, and borrowing from each other, “the copyist, driven to complete one thousand and one nights, kept adding folk tales, fables and anecdotes from Indian, Persian and Turkish, as well as indigenous sources, both from the oral and from the written traditions” (Nights xv). The tale of Sinbad is one such addition (the adventure is old, but its inclusion in The Arabian Nights is not). “The Story of Aladdin and the Magic Lamp” is actually a forgery written by a Frenchman named Galland and then translated into Arabic by a Syrian living in Paris to make it seem authentic, as evidenced by the French syntax and certain turns of phrase (Nights xvi).

The Syrian manuscripts attempted to preserve and reproduce the “original” which stopped at two hundred and seventy-one nights but the Egyptian branch of manuscripts, Haddawy tells us in the introduction, “shows a proliferation that produced an abundance of poisonous fruits that proved almost fatal to the original” (Nights xv). Haddawy calls such additions “poisonous fruit” because he feels they destroyed its Arabic homogeneity. Besides deleting, modifying, adding, and borrowing from each other, “the copyist, driven to complete one thousand and one nights, kept adding folk tales, fables and anecdotes from Indian, Persian and Turkish, as well as indigenous sources, both from the oral and from the written traditions” (Nights xv). The tale of Sinbad is one such addition (the adventure is old, but its inclusion in The Arabian Nights is not). “The Story of Aladdin and the Magic Lamp” is actually a forgery written by a Frenchman named Galland and then translated into Arabic by a Syrian living in Paris to make it seem authentic, as evidenced by the French syntax and certain turns of phrase (Nights xvi).

Freud expanded the concept of the pleasure principle, as he developed his theory of the death drive, into a broader, more inclusive life drive, which he associated with Eros, the Greek god of sexual love: “the libido of our sexual instincts would coincide with the Eros of the poets and philosophers which holds all living things together” (Freud, “Beyond” 619). Eros represents not only the sexual instincts, but thirst, hunger, self-preservation, reproduction, and creativity. Shahrazad, who holds all the living tales of the book together, is “intelligent, knowledgeable, wise and refined. She had read and learned” (Nights 15). This educated woman approaches her father, the vizier, and demands that he offer her to the killer king.

Freud expanded the concept of the pleasure principle, as he developed his theory of the death drive, into a broader, more inclusive life drive, which he associated with Eros, the Greek god of sexual love: “the libido of our sexual instincts would coincide with the Eros of the poets and philosophers which holds all living things together” (Freud, “Beyond” 619). Eros represents not only the sexual instincts, but thirst, hunger, self-preservation, reproduction, and creativity. Shahrazad, who holds all the living tales of the book together, is “intelligent, knowledgeable, wise and refined. She had read and learned” (Nights 15). This educated woman approaches her father, the vizier, and demands that he offer her to the killer king.

The sexual instinct, which Freud said is so hard to “educate,” can be carried to such extremes that pleasure becomes destructive, even self-destructive. From the point of view of self-preservation, Freud writes, the pleasure principle is “from the very outset inefficient and even highly dangerous” (Freud, “Beyond” 597). The prologue, which establishes the frame story of King Shahrayar and Shahrazad, is dripping with destructive sexuality.

The sexual instinct, which Freud said is so hard to “educate,” can be carried to such extremes that pleasure becomes destructive, even self-destructive. From the point of view of self-preservation, Freud writes, the pleasure principle is “from the very outset inefficient and even highly dangerous” (Freud, “Beyond” 597). The prologue, which establishes the frame story of King Shahrayar and Shahrazad, is dripping with destructive sexuality.