An overview of major themes, conventions, and motifs in metafiction, which is basically fiction about fiction or fiction that is somehow self-reflective. This summary will also serve as a guide to some of the posts I have written.

a.k.a. Ronosaurus Rex

An overview of major themes, conventions, and motifs in metafiction, which is basically fiction about fiction or fiction that is somehow self-reflective. This summary will also serve as a guide to some of the posts I have written.

At the end of the 1941 John Huston film The Maltese Falcon, based on the Dashiell Hammett novel, Sergeant Tom Polhaus asks Sam Spade about the heavy, black statuette of a falcon that was the cause of all the mystery and murder.

“Heavy,” he says. “What is it?”

Our hard boiled detective, Sam Spade, replies, “The, uh, stuff that dreams are made of.”

Continue reading “The Stuff That Dreams are Made Of: The Real, the Unreal, and the Maltese Falcon”

We don’t just speak with our mouths. We also speak with our bodies, our hands, our faces, our eyes, our respiratory systems, our lips, our tongues, our mouths, our brains. Various sayings emphasize the importance of these body parts in the production of language. Making faces. Her eyes spoke volumes. Hot air. Words dripped from her lips like honey. Mother tongue (implying that the language gives birth to the person). Mouthing off. Getting something off your mind. We used to talk about venting the spleen, letting out our angry feelings, but the truth is we don’t use the spleen. Speaking involves only certain parts of the body, so “I” tends to represent those parts.

We don’t just speak with our mouths. We also speak with our bodies, our hands, our faces, our eyes, our respiratory systems, our lips, our tongues, our mouths, our brains. Various sayings emphasize the importance of these body parts in the production of language. Making faces. Her eyes spoke volumes. Hot air. Words dripped from her lips like honey. Mother tongue (implying that the language gives birth to the person). Mouthing off. Getting something off your mind. We used to talk about venting the spleen, letting out our angry feelings, but the truth is we don’t use the spleen. Speaking involves only certain parts of the body, so “I” tends to represent those parts.

Continue reading “What Parts of Your Body Do You Speak With?”

A name is not a person, nor is it simply a reference to that person; it is a description that influences behavior. Michel Foucault stated that “one cannot turn a proper name into a pure and simple reference. It has other than indicative functions; more than a gesture, a finger pointed at someone, it is the equivalent of a description” (105). If a name, rather than being a “reference” is a “description,” we need to ask ourselves what names describe.

The Non-Existence of Nonfiction

In my book Narrative Madness, edited by Katie Fox, I showed that nonfiction is an impossibility since every text and utterance requires the invention of a fictional speaker who is never the whole person; it filters meaning through the speaker’s or writer’s name, uses narrative language which influences perception and behavior, relies on man-made symbolic code, necessitates the selection of subjectively interpreted facts while overlooking vast amounts of information, organizes information in artificial ways, redirects the future through a present discussion of the past, acts upon world, community and self rather than merely reporting on them, involves imperfect mindreading and empathy games, utilizes preexisting forms and genres which affect content and meaning, channels voices of predecessors who have previously used the language and textual resources, constructs a reader or listener, and requires recreation and performance by the actual reader or listener.

In my book Narrative Madness, edited by Katie Fox, I showed that nonfiction is an impossibility since every text and utterance requires the invention of a fictional speaker who is never the whole person; it filters meaning through the speaker’s or writer’s name, uses narrative language which influences perception and behavior, relies on man-made symbolic code, necessitates the selection of subjectively interpreted facts while overlooking vast amounts of information, organizes information in artificial ways, redirects the future through a present discussion of the past, acts upon world, community and self rather than merely reporting on them, involves imperfect mindreading and empathy games, utilizes preexisting forms and genres which affect content and meaning, channels voices of predecessors who have previously used the language and textual resources, constructs a reader or listener, and requires recreation and performance by the actual reader or listener.

It is all fiction. All of it.

Continue reading “An All-Encompassing Definition of Reality: The Conclusion to Narrative Madness”

Since we humans construct our narratives and memories socially, we could ask, “Do we have a collective memory?” Frederic Bartlett, often called the first experimental psychologist, criticized the concept, since “collective memory” seems to suggest a group brain. Societies don’t have brains. We must understand group memory, then, as distributed in the minds of individuals, in discourse, and in symbolic records. “Collective memory” is just a metaphor and taking it too literally is sign of narrative madness.

Since we humans construct our narratives and memories socially, we could ask, “Do we have a collective memory?” Frederic Bartlett, often called the first experimental psychologist, criticized the concept, since “collective memory” seems to suggest a group brain. Societies don’t have brains. We must understand group memory, then, as distributed in the minds of individuals, in discourse, and in symbolic records. “Collective memory” is just a metaphor and taking it too literally is sign of narrative madness.

The simulation theory takes the theory of mind a step further. Instead of trying to guess what others are thinking, we humans put ourselves in the other’s shoes, as the saying goes, in order to feel what the other is feeling.

(An extract of my book Narrative Madness, edited by Katie Fox, which you can get at narrativemadness.com or on Amazon.)

The Machiavellian Prince of Primates

Many other species are social as well, so why didn’t they develop sophisticated systems of symbolic communication? Primate societies developed language because of the exaggerated complexity of our manipulative social interactions. The MIT Encyclopedia of Cognitive Sciences says that “primate social relationships have been characterized as manipulative and sometimes deceptive at sophisticated levels” (Wilson and Kiel). Writes Kerstin Dautenhahn, biologist and professor of computer science, paraphrasing Frans de Waal, “Identifying friends and allies, predicting behavior of others, knowing how to form alliances, manipulating group members, making war, love and peace, are important ingredients of primate politics.” A hominid skilled at manipulation would be better suited than its more submissive counterparts to win resources, sex and power.

Many other species are social as well, so why didn’t they develop sophisticated systems of symbolic communication? Primate societies developed language because of the exaggerated complexity of our manipulative social interactions. The MIT Encyclopedia of Cognitive Sciences says that “primate social relationships have been characterized as manipulative and sometimes deceptive at sophisticated levels” (Wilson and Kiel). Writes Kerstin Dautenhahn, biologist and professor of computer science, paraphrasing Frans de Waal, “Identifying friends and allies, predicting behavior of others, knowing how to form alliances, manipulating group members, making war, love and peace, are important ingredients of primate politics.” A hominid skilled at manipulation would be better suited than its more submissive counterparts to win resources, sex and power.

All narratives are patterns, but all patterns aren’t narratives, unless they suggest character, setting and action. Animals look for and find patterns. So, we should ask, do animals produce narrative?

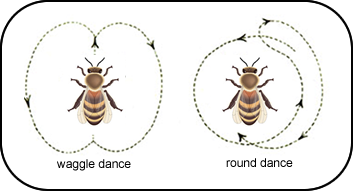

Well, yes. The language of the bees still astounds scientists. Bees communicate symbolically in the form of a dance, passing on information about distance, difficulty and value of potential food sources. They dance in the present about past experiences in order to exploit future resources. Other bees do their little dance, explaining alternative sources of pollen, and then somehow the bees come to a decision about the best source. An insect, a creature from the lower orders – far down the hierarchy of animals (at the top of which we have placed ourselves) – can clearly tell stories and make value judgements about them. (Read all about it in biologist and sociologist Eileen Crist’s article “Can an Insect Speak? The Case of the Honeybee Dance Language” [2004].) The idea is so astounding that I don’t even know what to do with it. I will just move on to dogs, with whom I can converse more easily.

Well, yes. The language of the bees still astounds scientists. Bees communicate symbolically in the form of a dance, passing on information about distance, difficulty and value of potential food sources. They dance in the present about past experiences in order to exploit future resources. Other bees do their little dance, explaining alternative sources of pollen, and then somehow the bees come to a decision about the best source. An insect, a creature from the lower orders – far down the hierarchy of animals (at the top of which we have placed ourselves) – can clearly tell stories and make value judgements about them. (Read all about it in biologist and sociologist Eileen Crist’s article “Can an Insect Speak? The Case of the Honeybee Dance Language” [2004].) The idea is so astounding that I don’t even know what to do with it. I will just move on to dogs, with whom I can converse more easily.

Continue reading “Do Animals Tell Stories?: The Narrative Abilities of Animals”

Narrative is a Very Limited Selection of So-Called Facts

Since language is inherently narrative and its stories strongly influence our perception and actions, it is important to understand what narrative is.

Since language is inherently narrative and its stories strongly influence our perception and actions, it is important to understand what narrative is.The word “narrative,” from the French narratif, began appearing in the English language in the early 1500s, referring to parts of a legal document laying out “alleged or relevant facts” (Oxford English Dictionary). The word “alleged” reminds us that all facts may be challenged in a court of law. A fact is not a fact until it has been proved. Even then, a legal decision is open to appeal. In many fields, including science and history, “facts” are frequently disputed and reinterpreted.