We are flooded with narrative, drowning in astronomical numbers of stories from paperbacks, movies, newspapers, television, magazines, fan fictions, computer games, and, most of all, the Internet. How can we cope with these stories? What do we do with them?

We are flooded with narrative, drowning in astronomical numbers of stories from paperbacks, movies, newspapers, television, magazines, fan fictions, computer games, and, most of all, the Internet. How can we cope with these stories? What do we do with them?

Meta-awareness is more important more than ever, if we are to understand our storied universe. Yet how can we know what is real with reality TV on every channel? Most of us are smart enough to know that the presence of a camera always causes people to act differently than they would otherwise. Although reality TV is realer than a sit com, we recognize that it is not as real as a news broadcast.

Continue reading “Relevance of Metafiction in the Age of Information”

It might seem that I am trying to demonstrate the unreality of reality. Many others have done so, including Taoists, Hindus and Buddhists. Jews, Christians and Muslims, following Plato’s lead, think God’s ideal realm is realer than this world. Religious people are not the only ones to call reality an illusion. Ludwig Wittgenstein said, “The limits of my language mean the limits of my world,” and Jacques Derrida suggested, “There is nothing outside the text.”

It might seem that I am trying to demonstrate the unreality of reality. Many others have done so, including Taoists, Hindus and Buddhists. Jews, Christians and Muslims, following Plato’s lead, think God’s ideal realm is realer than this world. Religious people are not the only ones to call reality an illusion. Ludwig Wittgenstein said, “The limits of my language mean the limits of my world,” and Jacques Derrida suggested, “There is nothing outside the text.”

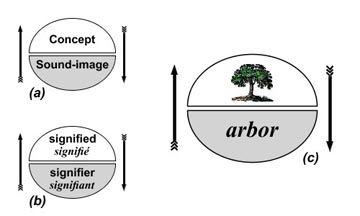

At the beginning of the last century, Ferdinand de Saussure severed language from reality. In his Course in General Linguistics, he explained that a sign is made up of two parts: the signifier and the signified. The signifier is a word, a set of sounds, sometimes represented by letters. The signified is what the signifier arbitrarily refers to. Unfortunately for those who want language to be a transparent window on the world, the signified is not an external object, but a subjective concept.

At the beginning of the last century, Ferdinand de Saussure severed language from reality. In his Course in General Linguistics, he explained that a sign is made up of two parts: the signifier and the signified. The signifier is a word, a set of sounds, sometimes represented by letters. The signified is what the signifier arbitrarily refers to. Unfortunately for those who want language to be a transparent window on the world, the signified is not an external object, but a subjective concept.

This introduction to Donald Barthelme’s short story “The School” is non-fiction. Non-fiction means “not fiction.” Fiction, as you have learned, is a story that is “not true.” In other words non-fiction, on a linguistic level, is “not not-true.” This means, logically, when you cancel out the negatives, that the non-fictional information I am about to give you, is — I am very pleased to say — true.

This introduction to Donald Barthelme’s short story “The School” is non-fiction. Non-fiction means “not fiction.” Fiction, as you have learned, is a story that is “not true.” In other words non-fiction, on a linguistic level, is “not not-true.” This means, logically, when you cancel out the negatives, that the non-fictional information I am about to give you, is — I am very pleased to say — true.