Does Pynchon’s novel mean something or am I crazy?

The heroine, Oedipa Maas, has a similar question. A former lover, Pierce Inverarity named her the executor of his considerable estate. Rather than bequeathing her money or property, he has saddled her with a long, legal process that she does not understand. As she is not a lawyer and has had little contact with Inverarity for many years, the naming of her Executor is puzzling. Was Inverarity trying to tell her something, or was it just one of his bizarre whims? Was he playing a practical joke on her, or was he hinting at a secret society?

The heroine, Oedipa Maas, has a similar question. A former lover, Pierce Inverarity named her the executor of his considerable estate. Rather than bequeathing her money or property, he has saddled her with a long, legal process that she does not understand. As she is not a lawyer and has had little contact with Inverarity for many years, the naming of her Executor is puzzling. Was Inverarity trying to tell her something, or was it just one of his bizarre whims? Was he playing a practical joke on her, or was he hinting at a secret society?

Continue reading “Message or Madness?: Thomas Pychon’s “The Crying of Lot 49””

It might seem that I am trying to demonstrate the unreality of reality. Many others have done so, including Taoists, Hindus and Buddhists. Jews, Christians and Muslims, following Plato’s lead, think God’s ideal realm is realer than this world. Religious people are not the only ones to call reality an illusion. Ludwig Wittgenstein said, “The limits of my language mean the limits of my world,” and Jacques Derrida suggested, “There is nothing outside the text.”

It might seem that I am trying to demonstrate the unreality of reality. Many others have done so, including Taoists, Hindus and Buddhists. Jews, Christians and Muslims, following Plato’s lead, think God’s ideal realm is realer than this world. Religious people are not the only ones to call reality an illusion. Ludwig Wittgenstein said, “The limits of my language mean the limits of my world,” and Jacques Derrida suggested, “There is nothing outside the text.”

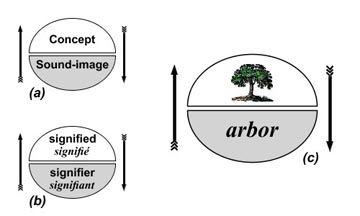

At the beginning of the last century, Ferdinand de Saussure severed language from reality. In his Course in General Linguistics, he explained that a sign is made up of two parts: the signifier and the signified. The signifier is a word, a set of sounds, sometimes represented by letters. The signified is what the signifier arbitrarily refers to. Unfortunately for those who want language to be a transparent window on the world, the signified is not an external object, but a subjective concept.

At the beginning of the last century, Ferdinand de Saussure severed language from reality. In his Course in General Linguistics, he explained that a sign is made up of two parts: the signifier and the signified. The signifier is a word, a set of sounds, sometimes represented by letters. The signified is what the signifier arbitrarily refers to. Unfortunately for those who want language to be a transparent window on the world, the signified is not an external object, but a subjective concept.

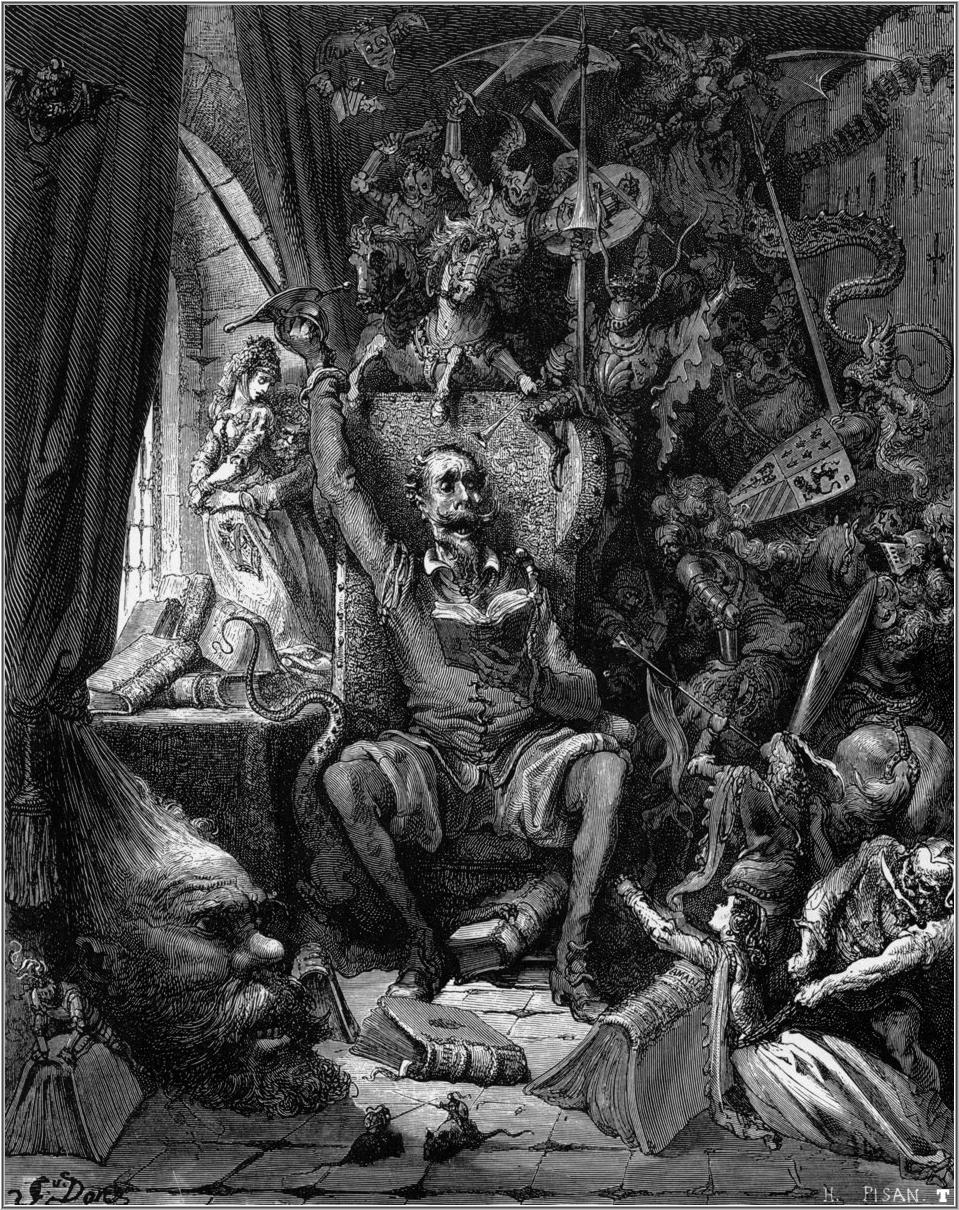

Andre Gide adopts the heraldic term mise en abyme, or a shield shown in the center of a shield, to describe a work within a work, like The Mousetrap in Hamlet, but Gide ultimately rejects such examples because The Mousetrap does not represent Hamlet as a whole, but only the actions of the characters within the play (as I discuss in

Andre Gide adopts the heraldic term mise en abyme, or a shield shown in the center of a shield, to describe a work within a work, like The Mousetrap in Hamlet, but Gide ultimately rejects such examples because The Mousetrap does not represent Hamlet as a whole, but only the actions of the characters within the play (as I discuss in